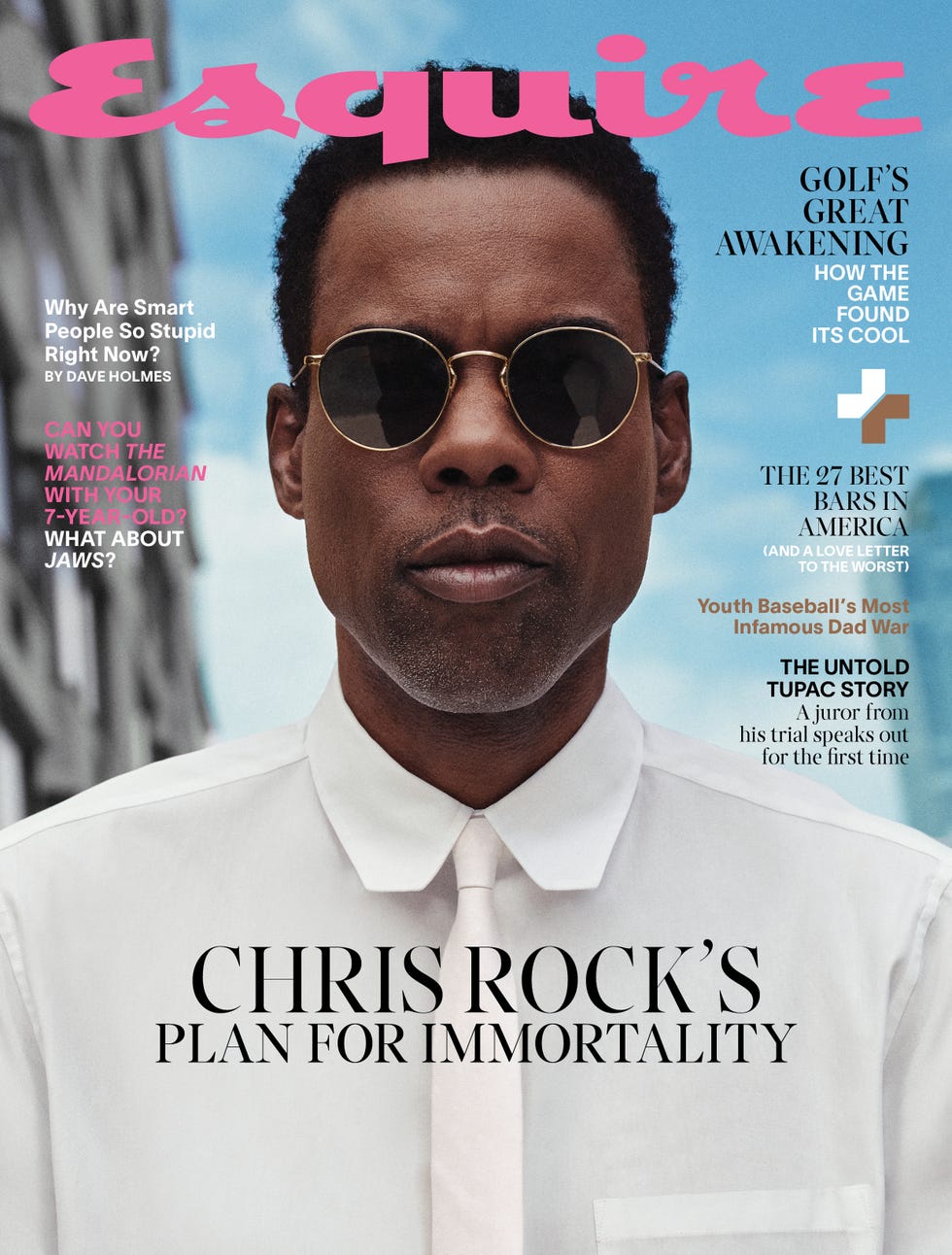

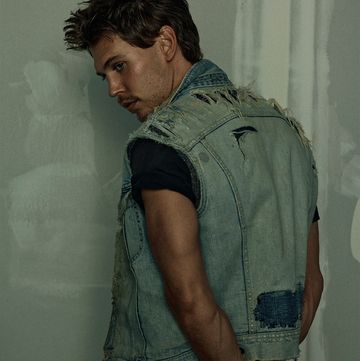

He stops on a pedestrian island to let traffic pass on Houston Street, and in that brief wait, I wonder if the people in the trundling cars spy one of the most famous comedians on earth under his mask and transition-lens glasses. No one, though, drops the window to shout his name or honk or jab an index in astonishment—Chris Rock granted a reprieve from living famous 24/7/365. Rock, who’s dressed casual in a hoodie and cargo pants and white Reebok Classic trainers, troops a half step ahead of me, a Tumi backpack slung over a shoulder.

We turn past a multitude of preschoolers enjoying the recess of their lives inside a fenced-in ball field and amble on up MacDougal. He slows his gait a bit. “The thing about this block is: It’s where Cosby worked. It’s where Joan Rivers worked. It’s where Woody Allen worked. It’s where Mort Sahl worked. All these motherfuckers,” says Rock. “It’s where Bob Dylan worked. Where Jimi Hendrix worked. You know what I mean? It’s kind of a mecca for pushing it.”

The street is narrow in normal times, but with the New York City Covid protocols for indoor dining, it takes careful maneuvering to avoid smacking, with our backpacks, people palavering at outdoor tables.

We stop outside the Comedy Cellar, the club that sits down a few scuffed steps from street level. A helluva lot of feet have walked down these steps and onto the stage inside, most on their way to nowhere, a few on their way to a career, and a tiny handful on their way to being remembered.

A poster with pictures of some of the memorable ones hangs on the wall. Rock scans the rows.

Let’s see: There’s Dave Chappelle, Bill Burr, Robin Williams.

You can’t see his mouth under his mask. Is he smiling? Pursing his lips to focus?

Wanda Sykes, Colin Quinn.

(Funny thing: When Rock needed a comedy club for a scene in his 2014 movie Top Five—which he wrote, directed, and starred in—he chose this very establishment, its name ever lit up in the round yellow bulbs of a Broadway marquee. The character he wrote for himself? A comedian who tries to transition to being a serious actor.)

Rock calls out the names of comedians I’ve never heard of. “Some of them, they’re not famous, but you know, they’re like great session musicians,” he explains. “Like all the musicians know this motherfucker can play some bass. You get five legends in the room and they’re all talking about this motherfucker you never heard of.”

He scans.

“And there you go,” I say, pointing at Rock’s photo, as if I’ve found Waldo.

The man earned his first acting credit in 1987 after Eddie Murphy caught his set at the Comic Strip (another New York institution) and cast him in Beverly Hills Cop II. Then boom: Saturday Night Live and In Living Color. Six comedy specials. A whole-ass sitcom based on his life. An HBO talk show. (That joint won an Emmy.) Starring role in an acclaimed Broadway play. Twice the Oscars host. Forty-something movies. Five billion dollars at the box office, if you add it all up.

An incontrovertible A-list résumé.

But . . .

This slim dude with the knowing eyes and the knife-sharp wit has somehow, at fifty-six, arrived at the belief that his place in the universe—of Black comedy, of comedy itself, of acting, of artistry, of defining the times in which he lives—is not quite set yet. That he must create more, more, more; that what he makes must be different, more challenging, and better, greater, superior.

Peep: In the past three years alone, he directed this year’s stand-up special Chris Rock Total Blackout—maybe his best ever—an extended cut of his 2018 special Tamborine. He anchored season 4 of the Emmy-winning crime drama Fargo, a shock to maybe everyone but him. Another shock: his starring role in Spiral: From the Book of Saw, the ninth installment of the Saw horror franchise out May 13. Then there’s his role in the untitled, mum’s-the-word David O. Russell film starring just about every A-list actor in Hollywood.

There’s the finished script of the next film he’ll direct.

There’s the nascent material for his next comedy special.

This article appears in the Summer 2021 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

On these steps, playing Where’s Chris on the poster, the same steps he shuffled down for the first time thirty-seven years ago, you think about how a comedian, an actor, a writer—any serious artist, which is what he is—must resist the temptation to marvel too long at what they’ve made, must instead meet the constant challenge of equaling if not surpassing it. Must answer again and again the crucial questions echoing evermore in the mind:

Does what I make matter?

And, by extension, do I?

Will I be remembered the next century?

Here’s a little secret: Part of Rock’s productivity has been keeping a journal handy for more than thirty-five years. “You read it over, and you’re like, Oh, that’s good for stand-up. Or Oh, that would be good for script,” he says in that inimitable voice of his. “And then there’s some other shit, you’re like, Oh, when I die, provided I don’t fuck up my career, people are going to think this shit’s really interesting.”

Now, what does it say about Chris Rock that he’s meticulous about recording his thoughts, on account of a part of him believes that he—that Chris motherfucking Rock—hasn’t yet made the mark he wishes to make on the world?

And what, goddamnyoume, does it say about the rest of us?

“I have this belief: Always eat before a meeting. Even a lunch meeting,” he says.

Ours are the only two Black faces in the hotel-lobby restaurant. He was sitting alone when I walked in.

“Because you don’t eat during the meeting?” I ask.

“Because hungry people say dumb shit. Because hungry people say things they regret.”

So we get food. We talk a little about family. Like:

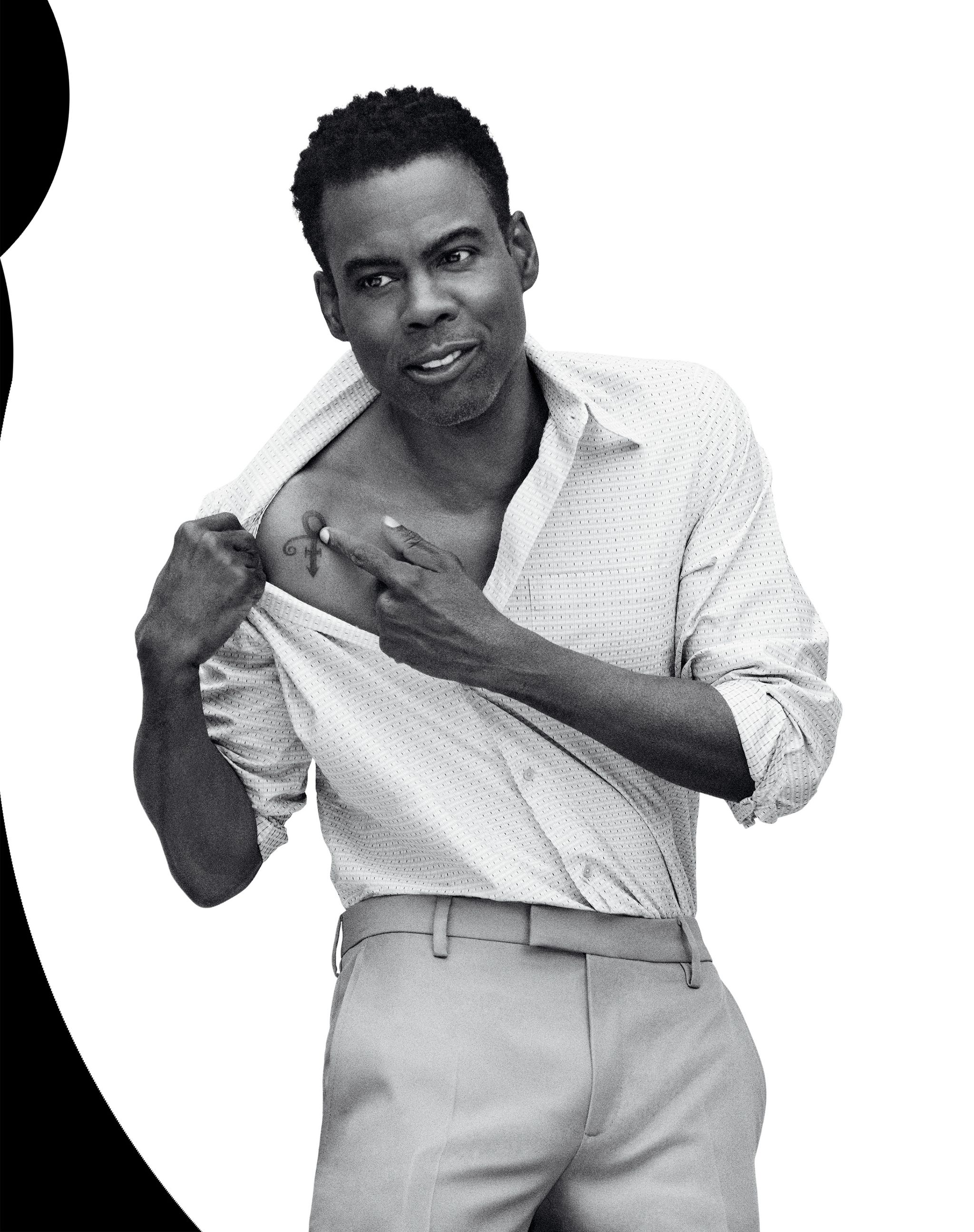

As part of a pact they made together, Rock got a Basquiat-inspired tattoo, on his left deltoid, with his eighteen-year-old daughter, Lola, last year, his oldest. By way of commiserating, I mention my oldest is also a daughter and nineteen, and that I have a portrait of her tattooed on my arm. And for a moment, we’re a mini girldad summit discussing, at bottom, the truth of being fathers to girls who, in too few beats of our naked hearts, have effloresced into young women.

It’s one thing to make art while your children are young and/or not its target audience.

It’s another thing to create when your kids are old enough to engage with what you make, are knowing enough to critique it.

It’s yet another to make work in a universe in which they’re also aware of prime examples of other art, can judge where your work ranks among that of your peers. And trust, don’t no self-respecting artist-dad want to make something his kids don’t respect. Or worse, something that pains them.

Rock recalls couple of years ago, he got a call to be in Lil Nas X’s video for “Old Town Road.” At the time, he had no idea who the hell Lil Nas X was, but he asked his youngest daughter and she implored him to say yes. “I have a focus group in my house,” he says. “I definitely run things by them. My daughters are all about ‘You got to stay relevant.’ They want me to work with relevant people.”

Tamborine was the first special he made since his two daughters—Zahra is seventeen—were little girls, also the first since he and their mother divorced after eighteen years of marriage. And those two topics are a crucial part of the show’s impact. Says the writer and producer Nelson George, one of Rock’s closest friends (they first worked together on the 1993 hip-hop parody CB4): “He named it Tamborine,the same as the Prince song—I think it speaks to mortality. Prince is one of Chris’s biggest heroes. And dude is gone. So the show is also reckoning with, you know, that there’s an end point to this shit.”

Tamborine might also be Rock at his most vulnerable on the stand-up stage, a contrast to the special of his that I’ve watched most, Bigger & Blacker (1999). That one begins with Rock swaggering onto the stage of the Apollo Theater in a black leather suit, his hair sheened, his ears aglint with diamond studs.

Believe me when I tell you, the Rock of Bigger & Blacker ain’t worried about a career end point.

“Bring the Pain changed my life,” says Rock of the 1996 special that thrust him mainstream. “The Oprah show, 60 Minutes. But you know, like Whitney Houston, there was a little bit of grumbling. Like, ‘White people like him too much.’ So it was like, I’ll show you motherfuckers. I’m going to play the Apollo. This is going to be bigger and blacker.” (It was taped the same year as the Columbine school shooting and opens with a long bit about shootings in largely white schools. “When I’s a kid, they used to separate the crazy kids from everybody. When I’s a kid, the crazy kids went to school in a little-ass bus, they had a class at the end of the school, and they used to get out of school at 2:30—just in case they went crazy, they would only hurt other crazy kids! And we was all safe. But now the world is coming to an end! You’re gonna have little white kids saying, ‘I wanna go to a Black school where it’s safe!’ ”)

If I hadn’t seen Bigger & Blacker umpteen times, I’d question whether that kind of bravado could exist in the dude sitting across from me now picking over his eggs, a man whose thick brows and midday stubble are flecked with gray. “Comedians or artists, whatever, you do this thing which naturally puts you on a stage. So you’re always a little higher than the audience,” says Rock, gesturing. “But the better the performance, the lower the stage gets.”

Rock’s friend Maya Rudolph recalls dining with him and some friends during his preparation for one of the Oscars shows. Near the end of dinner, Rock announced he was headed to the Comedy Store to do a set. “The reason why I bring that story up is because Chris went from being the guy at dinner to the guy saying, ‘We’re going to go do this’ to the guy walking in and doing that thing. He’s obviously performing, but it’s the same shit he told you ten minutes ago, before he went onstage. And it’s very interesting to watch someone who knows the weight and the gravity of what they’re saying—that what they’re saying is good enough for you across the table at a restaurant, or millions of people watching at home, in the exact same breath and exact same way.”

One of the funniest humans of all time has a habit of touching a cupped hand to his face in contemplation for what can seem like long minutes. “Comedy’s a deadly serious business,” says Lorne Michaels, Saturday Night Live creator and comedy kingmaker. “And Chris is a thinker.”

At one point during lunch, Rock pulls out his phone and reads off a list of books, both finished and on the TBR pile: Fake Accounts, the new novel by Lauren Oyler, which gets into Internet secrecy and online personas; The Basic Laws of Human Stupidity,an economist’s 1976 treatise on the potential for idiots to hold power; The Body Keeps Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, the best seller; Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby. “You know what’s great? Rereading books,” he says, his voice buoyant. “It’s one of the most fun things you do, because you’re reading the book as a different person.”

And music. Red Hot Chili Peppers frontman Anthony Kiedis, another of Rock’s aces, says, “Chris is one of the single biggest fans of music in general that I’ve ever met. A lot of people are deep into their jams earlier in life, and then they kind of lose touch with that wonder and that fascination with songs and music. . . . That whole infinitely healing energy of music of all varieties—Chris still has that.”

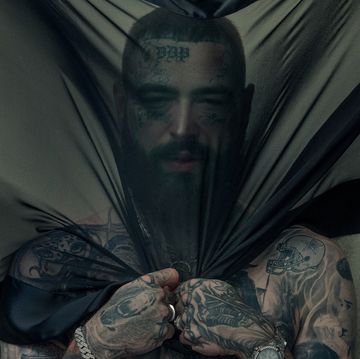

Rock’s polymath tendencies extend even to horror flicks. It was he who pitched Lionsgate top brass on doing a Saw with a few jokes, and he’s not just a fan but a student of horror. “A lot of times you meet with people and they say, ‘Oh, I love the horror genre,’ and you can tell if they’re bullshitting,” says Spiral director Darren Lynn Bousman. “That was not him at all. He was giving very obscure references to movies, as well as very detail-oriented thoughts on the previous Saw films.”

Rock plays a righteous detective in a corrupt department. It’s a Saw film, so there’s the requisite violence and gore, but it’s also a cultural critique, with canny timing. “Coming in this time, I think the idea was about institutions and corrupt institutions, and the police not being the only corrupt institution,” says Bousman. “That institution could be pharma, it could be churches, it could be police. But instead of going after individuals, we were going after institutions.”

So yes, there is the cultural import of the project. And there is Rock’s goal of pushing oneself as an artist. But Rock will still bust guts. “There’s a scene where Chris has this dramatic encounter in the police station right after he finds out his partner died, and no one’s taking it seriously, and he wants the case,” says Bousman. “He comes in and he’s screaming and going off and gets really emotional. We do it in one extremely long take—it’s silent at the very end, and he’s got tears coming down his cheek. And everyone on the set claps and they’re like, ‘Oh my God.’ And he looks directly at the camera and goes, ‘Lest no one forget: I was in Pootie Tang. So what I’m saying is, I have range.’ ”

What a day for a walk it is: spring balm, a blue sky strung with soft white clouds, the city sounding more song than cacophony. We stroll down Prince Street, emboldened with the vax-gifted aplomb that this walk won’t be the death of us.

On West Broadway, a strange sight gives us pause: a phalanx of some thirty uniformed NYPD officers gathered on the north and south sides of the intersection.

The light changes for us to walk, but Rock waits, sussing out the scene.

“Something’s going down,” Rock says.

A white woman and a young white dude bop by with what seems no doubt whatsoever about being protected and served.

He just watches. Then:

“Oh! What’s his name? The verdict’s today. Did the verdict come in? Yeah, the verdict’s today, and you got all the designer stores over here.”

Ex-officer Derek Chauvin. Minneapolis. The jury is coming back in soon.

“Maybe they’re about to start boarding them up,” I say.

“Yeah. That’s what’s up,” he says. “That’s what’s going down.”

He pulls out his iPhone to check for alerts. And just that fast, our walk is more significant. Just that quick, I can imagine telling the story years later, where I was and who I was with when the Chauvin verdict came in. Then, kaboom, a hearttick later, it also hits me that the tension of this moment puts Rock and me at greater risk than our average risk, which even for us middle-aged Black men—wearing masks—is pretty darn dangerous.

(The moment reminds me of his opening monologue at the 2020 Oscars. “Mahershala Ali is here tonight. Mahershala has two Oscars,” says Rock, looking so fresh and so clean in his tux. “You know what that means when the cops pull him over—nothing!”)

We could walk another block—a detour I almost suggest—but don’t. Instead, we huff across the crosswalk, and as we pass, I hear them blathering, the cops, see a few of their faces looking a bit too smug for the circumstances.

When we chat the next week about the encounter, I mention to Rock that I was wary that if something broke out . . .

He says, “Well, you know, in moments of chaos, we’ll always be just two Black guys walking down the street.”

Picture a young, Afroed Chris Rock—Chrissy to his siblings—helping his father load bundles of the New York Daily News onto his delivery truck at the paper’s Brooklyn plant, a colossal eight-story building flanked by two low wings in Prospect Heights. Mid-seventies. Picture the pair working without words, grown satisfied with grunts of effort as a language. Picture Rock as a frail teen a few years later, him bolting out of the family’s brownstone in the small blue-black hours to fetch a bundle his father has left him to sell. Picture him jaunting to a nearby subway stop and hawking his inky treasure till the whole stack sells.

“That was a great hustle,” Rock says. “It was me, my siblings, sometimes my friend. But a lot of times it was just me, man, because who the fuck wants to get up at 4:30 in the summer?”

His father was living some version of the American dream. Rock’s Fargo character depicts what that dream looked like seventy years ago and the ways in which Black people have tried to reap its rewards from land that proved barren for us but fecund as fuck for others. With Rock as its star, the show also serves as a critique of America’s particular brand of racism. Says Noah Hawley, Fargo’s white creator and showrunner, “There is that violence to the Black experience in America. You’re told to succeed, but you’re not given the tools with which to succeed—and then you’re judged for not succeeding. That becomes an impossible setup on some level. It makes it absurd, but it’s not funny. The irony of it, without humor, is just violence.”

Like untold essential aspects of Black culture, Black comedy was born in the antebellum South—how else to survive the malevolence that was chattel slavery? In their off-hours, enslaved Black people would gather on the plantation to entertain themselves. Before long, white people were avid spectators of the gatherings, the irony being that those enslaved Black folks were often mocking their white “masters,” the paradox being that those performances helped birth the stereotype of the coon, and concomitant, the era of minstrelsy: white men, the most famous being Thomas “Jim Crow” Rice, smearing their faces with burned cork and deriding Black people in caricatures. It took almost one hundred years after the Civil War (in which Rock’s great-great-grandfather fought) for mainstream America, aka white people, to allow Blacks on their stages.

Would there be a Chris Rock without the ribald Redd Foxx, who in the 1950s became one of the first Black men to cut a comedy album? Would there be a Chris Rock without the radical Dick Gregory, who in 1961 became the first Black comedian to perform in the Playboy Club? Would there be a Chris Rock without Bill Cosby breaking down Jim Crow barriers when Rock was still a boy? Would we have a Chris Rock without Richard Pryor (who Rock calls the GOAT) daring to transform what a comedian could say and do? Would we have known Chris Rock for as long as we have without Eddie Murphy owning SNL and the eighties?

And where does he sit in all this?

Check the record, Rock ranks high on the lists of all-time great comedians—Comedy Central (no. 5), Rolling Stone (no. 5), Paste (no. 2). He matters. Still, don’t go offering him any lifetime-achievement awards. “I get these offers and I always turn them down,” he says. “I’m always like, you can’t be in the Hall of Fame and play at the same time.” And for whosoever has the idea, it’s best not to ask where he judges himself among his forebearers and peers. “What’s my spot?” he says. “I’m just working. One day, we’re going to look and it’s going to be like, Oh, I did a lot of work. That’s it. I did a lot of work. I’m just working, man.”

Just a few blocks from the restaurant, Rock points to the top floor of a building in SoHo and informs me that it’s his new condo. Go figure, it’s the first time he’s ever lived in Manhattan. Which is interesting in itself—why he’s living in New York.

“I’m looking for that thing where, Stevie Wonder is already Stevie Wonder, but then he moves to New York, and now it’s Innervisions,” he says. “He’s a whole new guy. He’s already a superstar. He’s already done My Cherie Amour and Signed, Sealed, Delivered. And Michael Jackson, same thing. Michael Jackson is fucking Michael Jackson. But then he moves to New York, and now he’s doing The Wiz, and he’s hanging out with Quincy [Jones], and now you got Off the Wall andThriller. That shit’s all here. He’s living a lifestyle that can only happen in New York, and he made his best art.”

The answer to that question about why’s he still trying to prove himself even though his place in history is cement. Well, how about he ain’t trying to prove himself at all. How about he’s working, creating, ad infinitum, not because he wants to, really, but because he can’t not do it, because deep down he suspects we need it. “Chris Rock is more comedian than public intellectual, but the intellectual is definitely there behind his performance,” says Steve Martin, one of Rock’s heroes. “He is working it hard—and he has courage. He has courage to go public with those thoughts that, Oh, you’re not supposed to say that.”

We huff down the street, see people milling in and out of stores with bags in hand—let the revenge shopping begin—see delivery drivers with the backs of their trucks swung open, see a clique of drippy youngsters bopping by, something funny turning their laughter bright as the day. About three quarters of the folks on the street wear masks, including Rock and me, who assured each other before we stepped out of the restaurant that we’d both been vaccinated.

A homeless-looking brother, old enough to be Rock’s uncle, stops cold and cocks his head as though trying to x-ray Rock’s mask. “Hey, anybody ever tell you you look like Chris Rock?” he says, tilts his head the other direction, and squints. “Wait a minute, wait a minute,” he says, wagging a gnarled finger at Rock. “Are you Chris Rock?”

Rock pauses as if to consider an answer, but instead he rolls on without one. “I haven’t figured out the joke yet,” he says when I catch his stride. “It might even be in the next special. I don’t know. But I wrote on a piece of paper the other day: When the homeless know your name. It’s like, okay, talk about a fucking responsibility to the fucking world.”

The early-afternoon hectic of cars zooming and weaving and breaking and honking up Avenue of the Americas. Rock checks his watch and tells me he needs to cut out for his therapy appointment. He waves down a yellow cab so quick it seems impossible. We bump elbows before he climbs inside and disappears into the crush.