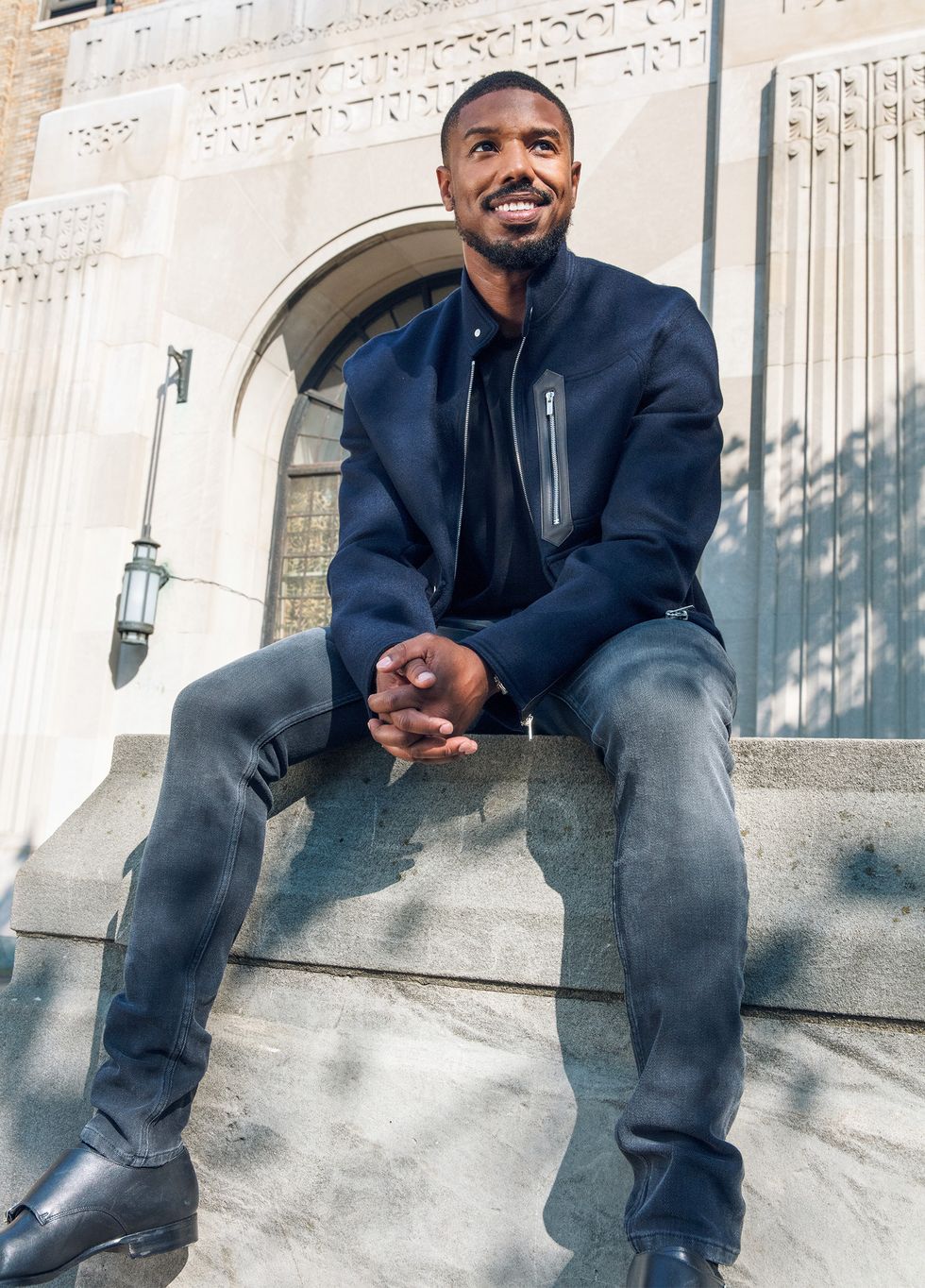

Up ahead, there’s a production moho (what industry folks call a mobile home) in the parking lot behind the school. The moho is hella conspicuous, which is a hazard of sorts, because megamoviestar Michael B. Jordan is inside it—with a team of people prepping him for his cover shoot—and the plan is to secret him around his old high school without the whole student body catching wind that he’s in the building and going apeshit.

One of the production team escorts me into the basement room that’s been repurposed for craft services, where I meet the photographer, Gio Valentine. Gio’s a black man, just like Jordan and me, which at once makes the pressure to do right by this assignment feel magnified.

If you’ve been on a photo shoot, you know there’s ever at least one unexpected problem to solve. One of today’s conundrums is how to find a speaker so Jordan can listen to music while he shoots. The best the school can offer is a decrepit CD/cassette-player contraption from the nineties. There’s a tiny summit held to figure where in Newark to cop a Bluetooth speaker.

Given the logistical goal of secrecy, members of the editorial team confirm, reconfirm, and reconfirm the reconfirmation of which route is the safest to ferry MBJ from the moho to the first location of the day: his old locker room. Ahead of MBJ’s entrance, I preview the route and notice it passes right by a lunchroom of boisterous teens, as well as past the gym, where through tall windows can be seen the varsity boys basketball team, dressed in their white-and-green uniforms—go Jaguars. The boys, who’ve been told they’ll be part of a photo shoot but have been deprived of all other details, are engaged in something between pure basketball antics and a layup drill.

There’s a full crew set up in the locker room when I enter. This locker room reeks of the locker rooms of my yore, and might not have been painted since MBJ was roaming the halls, hair braided and dressed in a tall white tee and über-capacious jeans, around the time he was playing the unforgettable Wallace in the first season of The Wire, before he was the cocky quarterback on Friday Night Lights, before the breakout lead role in Fruitvale Station, before he reignited the Rockyfranchise as Adonis Creed, before Black Panther heralded him to anyone who hadn’t seen him yet.

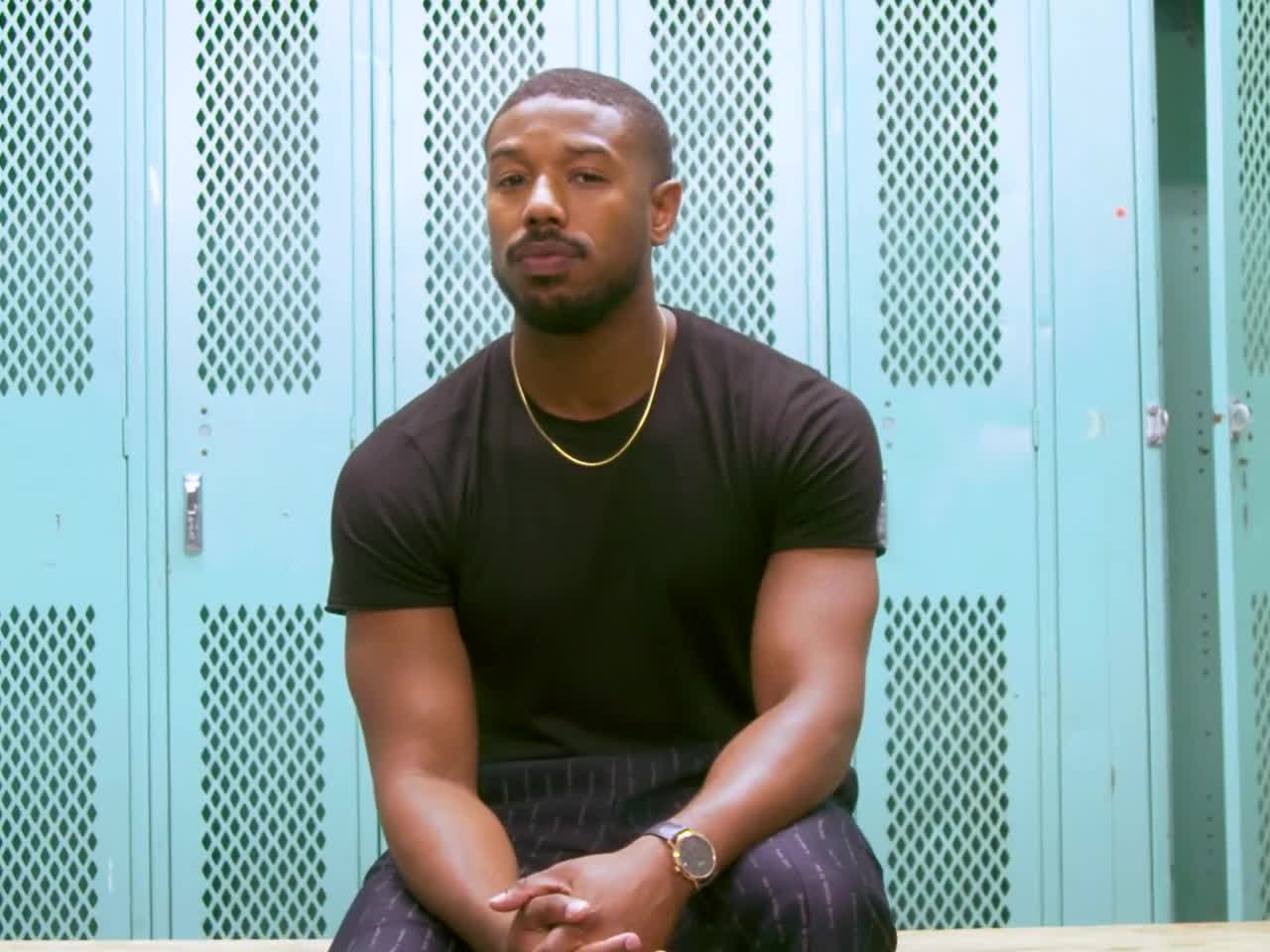

When word comes over the radio that Jordan’s ready, I am posted outside the locker room. Several students scuttle past, yelling, “Michael B. Jordan is here! Yo, Michael B. Jordan is here!” and cause no slight panic in the woman standing beside me. Jordan saunters into the locker room, seeming insouciant about his cover being blown, wearing a black T-shirt and striped slacks. He strolls around the room, smiles as he peeks in corners, opening and closing his old locker, confirming how little has changed. His videographer has a small speaker roped around his neck playing “Feels,” by Ed Sheeran featuring Young Thug and J Hus, and when I ask where’d they buy it, he says he had it the whole time.

They pose Jordan on one of the benches. Gio pops off several shots. MBJ gets up and checks the images on the monitor, offers feedback—a little preview of the director’s blood running through him. He takes his seat again, does more poses.

Once everyone’s satisfied, people are standing around, and someone hands him the head of the mascot’s suit. Michael Bakari Jordan, megamoviestar, Arts High class of ’05, sticks the huge jaguar on his own world-famous head.

Far from Newark, the director (Destin Daniel Cretton) of MBJ’s new movie (Just Mercy) brought the cast out on the stage before a screening. We were in the Elgin Theatre, a venue last-century decadent, with opera boxes and red velvet seats and a domed ceiling and walls adorned in ornate gold.

Out they strolled: the veteran Tim Blake Nelson, Rob Morgan (a scene-stealer if ever there was one), Oscar winner Jamie Foxx, Oscar winner Brie Larson. And to the loudest whoops and hollers and one loud marriage proposal, Jordan swanked on stage looking supercaliswagalistic in a silver-embroidered three-quarter-length black jacket, a button-down shirt so white it was neon white, tailored black slacks, and black pointed shoes with a glint of metal at the toe.

Just Mercy was adapted from a memoir by Bryan Stevenson, a lawyer and social-justice advocate who has devoted his life to fighting for justice for people behind the walls. The film details the true quest of Stevenson—that’s Jordan—to free an Alabama man named Walter McMillian (Foxx, at the top of his game), who was wrongly convicted of murdering a teenage white girl.

Jordan’s performance is the film’s engine.

There’s this one scene early on (and I hope this recounting is worth at least an itty-bitty spoiler) in which Stevenson visits McMillian in prison for the first time. Picture a young, Ivy-educated black lawyer from up north showing up in Alabama with the intention of getting a black man off death row. That first visit, a white CO orders Stevenson to a small room for a strip search, as a condition for meeting with his client—an astonishing, illegal condition, an order applied to millions of America’s incarcerated humans but here used to humiliate a black man viewed as a little too uppity with his suit and tie and his briefcase.

Stevenson, resigned, is shown stripping out of his suit jacket and shirt and loosening his tie. “Pants and underwear,” the CO sneers, and the camera goes tight on Stevenson’s face, rage twitching in his cheeks—in Michael Bakari Jordan’s cheeks.

For the uninitiated: A strip search requires the person to strip naked, bend over, spread their buttocks, and cough. While it’s touted as a way to keep contraband out of jails and prisons, the search is also no slight debasement. And trust and believe, I know of what I speak, for I spent more than a calendar in a state prison and felt no less human than when I was ordered to comply. All but impossible to forget standing buck naked in a cold concrete room, just-removed cuffs like phantoms on your wrist, one, two, three men looking on as you turn this way and that, lift the soles of your feet, show your palms, open your mouth and thrust out your tongue, as you turn your back on command, bend over, spread your ass, and cough. The first time it happened to me, I had the nerve to be incredulous, not realizing, when I entered the system, that I’d in many ways forfeited the right to govern my body.

Though Jordan had experienced the search only in the context of filming, to be present in that moment had to have been a kind of trauma, and believing that made me feel an unexpected connection to him. Yeah, he was an actor playing a part in a scene, but he was also using his talent and power—you can bet it was no accident—to show an injustice.

So it goes: Actors make choices—if they get to the point where they’re fortunate enough to be selective, anyway. An actor like MBJ can pick and choose. The question is, what does he do with that power? The question is, what kinds of stories does he choose to tell to the millions? MBJ has amassed real power in Hollywood, and needs to keep it to tell the stories he wants, but he also seems bent on not being of Hollywood.

How does a thirty-two-year-old black man navigate those dual aims?

The cast—and the real-life Stevenson—sat for a Q&A after the screening. Near the end of it, the interlocutor asked: Having played superheroes and villains, what does it feel like to tell a true story, where every gesture had been made by people who were living and breathing?

MBJ, who sat with immaculate posture, feet planted—none of that extra-extravagant leg-crossing business—and hands folded between his legs, peered for a beat or two at the floor, then out at the theater. “He’s a real-life superhero,” he said of Stevenson and touched his chin. “After I got a chance to really get to know him, and his story, and his work, I felt like I had a great deal of pressure to get it right. . . . And I felt honored to be able to carry that weight.” MBJ lowered the mic between his legs and cupped the head of it. He looked to one side of the stage and the other. He cast his eyes to the floor, and the audience clapped and cheered, cheered and clapped.

There was an after-party. Picture a swanky interior with VIP sections replete with couches, low tables stocked with buckets of ice-chilled bottles, lights just the right dimmed, several hosted bars, and dozens of black-vested waitstaff offering hors d’oeuvres from gleaming silver platters. The DJ spun at a level just low enough for talking without shouting. MBJ’s security detail: fit white guys in black suits, with close-cropped hair and a white cord spiraling from an earpiece into their shirt collar. You don’t want no smoke with the earpiece dudes.

He worked the room, snapped pictures and shared laughs with the ceaseless procession of folks vying for a moment of his time. At one point, MBJ bopped over to where Foxx, clad in a gray plaid suit and a fedora,

was commanding his own section. They leaned into each other, whispered something between themselves, and it must’ve been a hoot, because they slapped shoulders and threw back their heads and guffawed, an audience of dozens gawking all the while, their security hovering close.

MBJ floated around the shindig for another hour or so, during which time I never saw him drink. Near 1:00 a.m., he marched out with an entourage, including the earpiece dudes trooping in front of and behind him.

If you ask me, black men, at least the ones I know best, are obsessed with authenticity. A fake one, a perpetrator, a pretender, fugazy, fraudulent—all aspersions. But keeping it real, keeping it 100, being a real one, being the realest—aspirations. To be real is to live grounded in the world, eschew pretense, to thumb claims of entitlement. To be a Hollywood star, on the other hand, is to exist as a myth to the masses. There are beaucoup tales of movie stars who are ultra difficult, who’ve lost touch with the experiences of the common man, who begin to accept or have accepted their mythology. Or let me put it like this: Hollywood breeds the antithesis of real ones. Having up to that point only observed Jordan, I was unsure of what to expect, wasn’t sure if he’d let the glare of fame turn him solipsistic, wasn’t sure if my initial impression of him—as someone sincere, as an actor who’d achieved extraordinary fame and had managed to resist letting it overcome him—would hold true.

MBJ struts into the gym, and the varsity squad erupts in ooohs and aaahs.Some clap. Others point with a fist smashed to their lips.

Jordan ambles over to meet them, and they circle around him while the crew stands on the periphery.

The school principal, Mr. Pedro, moseys into the gym, emerald-blue-suited and booted, unfazed, or so it seems, by the present hullabaloo. Jordan hustles over to Mr. Pedro just as soon as he sees him, to hug and say a few words. Mr. Pedro is a family friend who worked at the school when Jordan and his siblings—his older sister, Jamila, and younger brother, Khalid—were students here.

Jordan is called back to the set. Mr. Pedro finds a perch in the bleachers, watching his former pupil out there on the floor with the current crop of multitalented preps. “Michael stood out as a person who had direction, who had a focus,” the principal says. “He was destined for this.”

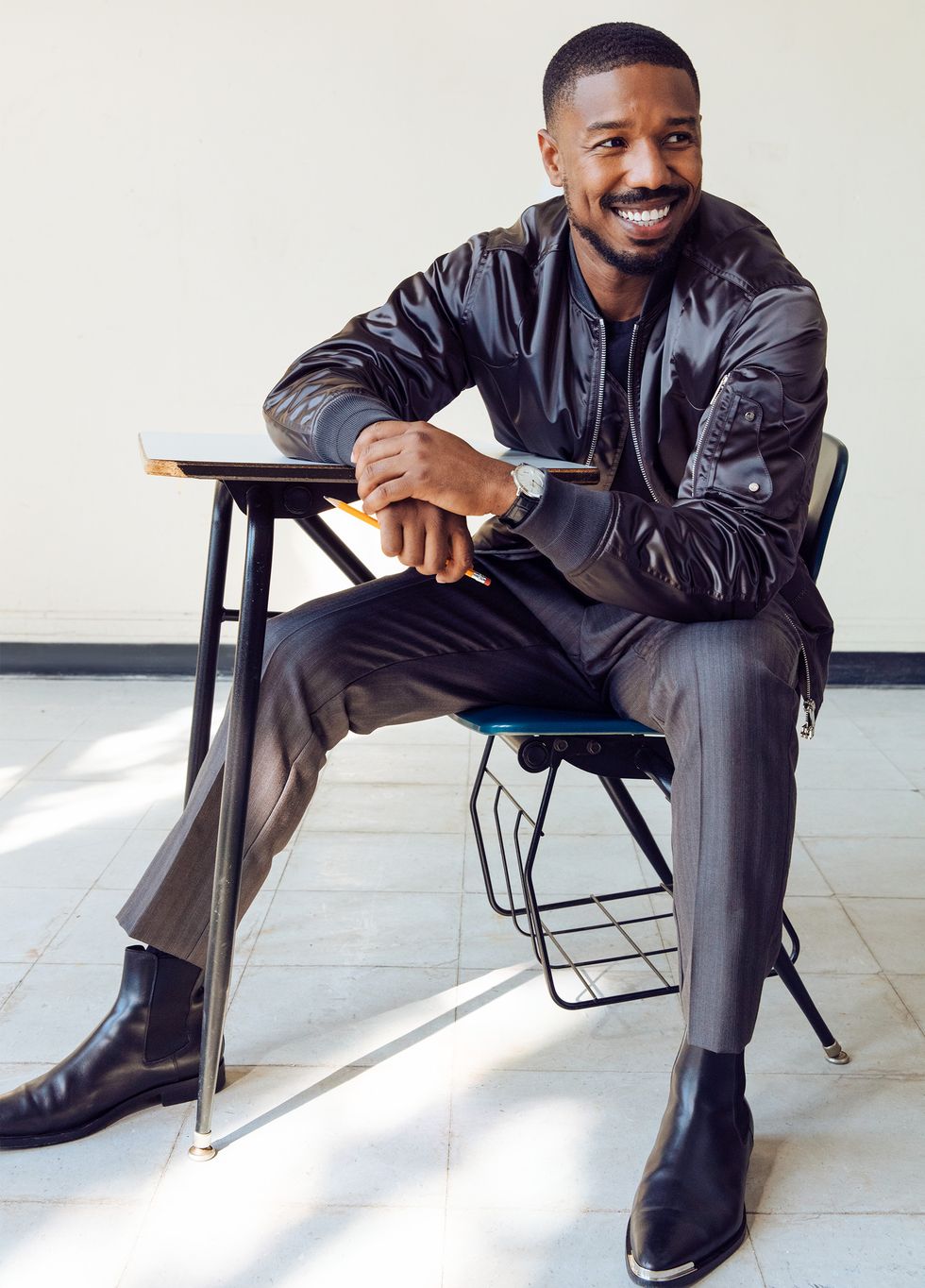

Jordan is having a blast being photographed with the squad, posing at the midcourt circle, in the bleachers, trading jokes and chopping it up in between. Once they’re done with the camera, the team goads him into shooting a jumper. He declines at first—something about his clothes and not having played in a while. But he succumbs with just a bit of pressure. He doffs his jacket and walks back onto the court, ball in hand. You can see where the tailor had to tack his pants to fit his slim waist.

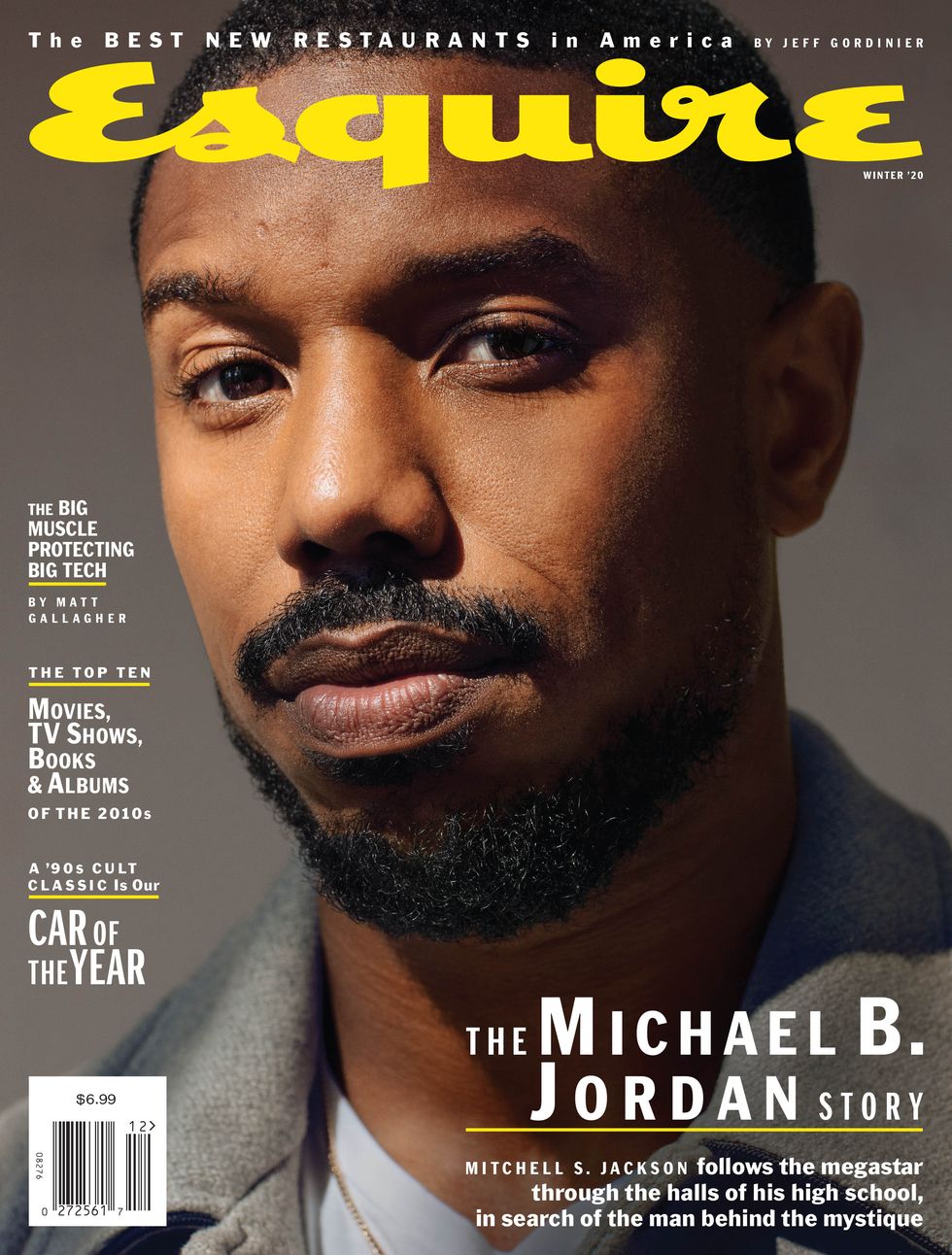

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue of Esquire.

Subscribe

See arms that look like boulders in the sleeves of his turtleneck. See shoulders the size of small mountains. And this is the dude who had to take time off from serious training to film Just Mercy so he could look like a regular Homo sapiens and not a demigod just bounding off the set of Black Panther. (As his trainer, Corey Calliet, says, “I had to let his body get back to its natural form of basic needs. I had to have him eat a lot of protein and live a normal life.”)

Jordan stops near the top of the circle and shoots, elbow tucked with nice extension. He misses, and the squad soundtracks the miss with raucous onomatopoeia. He takes another shot and misses that, too. He takes another and another, misses both. Then a man with a salt-and-pepper beard and polo shirt in school colors strolls onto the court, whispers something in Jordan’s ear, and stands by his side. Jordan bends his knees a bit and sinks his next shot. The squad applauds. The jump-shot whisperer is Jordan’s old coach, Mr. Kennis Fairfax. Coach Fairfax.

At just thirty-two, Jordan is a young OG as far as Hollywood goes. He was born in Santa Ana, California, the middle child of three kids, but raised in Newark by his parents, Donna Davis Jordan and Michael A. Jordan. His mother is a visual artist and former teacher, and his pops, a Marine and former affiliate of the Black Panthers, runs a food bank. “My artistic side, my emotional side, my intuition, being an empath—I get that from her,” Jordan says. “My discipline, my work ethic—I get that from my dad. So between the two of them, I got the right ingredients.”

His career began when his mother was at a doctor’s appointment and the receptionist encouraged her to shuttle him to an audition. Jordan started landing local modeling gigs posthaste, which pleased his mom, but his pops wasn’t so keen. “He was hesitant on the whole entertainment thing when I was younger,” says Jordan. “He used to say,

‘Bakari, you have to be serious about something. What are you serious about?’ ”

That skepticism endured until Jordan’s pops saw him on the set of Cosby, his first acting role. “He saw the respect I had from the crew, and I think that’s kind of what clicked, and he was like, Okay,” Jordan says.

In Fruitvale Station, Jordan took the role of Oscar Grant, a black man killed by a transit cop in Oakland. Grant is a returning citizen with a young daughter and a girlfriend who wants better for him. He’s been fired from his job and has been selling weed to provide for his family despite the chances of it landing him back in prison. Grant’s circumstances almost echoed the crucible of my own early twenties—as well as no few of my peers’—a period during which my time behind the walls seemed to consign me to dreaming no more than was practical and to years, if not a lifetime, of struggling.

That director was Ryan Coogler, then all of twenty-six years old. “The working conditions for Fruitvale were really intense,” says Coogler. “Through the intensity of the work, of the subject matter, and the limited resources that we had, we kind of forged a working rhythm and friendship as well.”

The pair reunited for Creed, the Rocky-franchise spin-off that turned MBJ into a sex symbol, two years later, in 2015, and again for Black Panther, the 2018 film that, with its billion-plus box-office gross and Oscar nomination for Best Picture, launched Jordan into the global-star stratosphere.

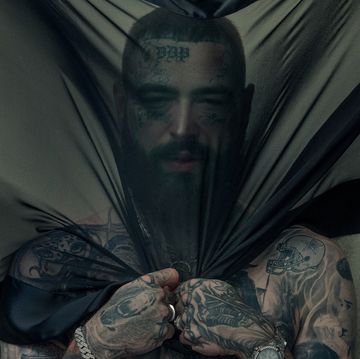

A superhero-franchise flick, yes, but Black Panther was also cultural critique, one that highlighted, among other things, the history of colonization, the plight of blacks in the Other America, and the sometimes fraught relationship between American-born blacks and our African kin. As Black Panther’s nemesis Killmonger, Jordan again played a character whose experiences reflected my own—and those of many I knew well—boys who felt orphaned, who seethed through their teens, some of whom, as young men, bought straps and invited reasons to use them or else carried them on their person as a means to survive. Some of us learned the wicked history of the Middle Passage, were told Africa was our homeland, but what did that mean when we—and four hundred years of forebears—had also been conditioned into disconnectedness from the diaspora? Shoot, Killmonger might as well have had the year 1619 tattooed inside his lip instead of a glowing Vibranium symbol.

For damn near twenty years now, Jordan has been making the experiences of American black men legible to the wide world. And I’d argue that doing so is an essential part of what keeps his feet planted on terra firma, even when he’s now a Hollywood elite.

Coach Fairfax, who remains close to Jordan’s parents, preaches the importance of Jordan staying connected to home. “The thing is, if you’re trying to be successful, and home don’t support you, what happens when the world turns its back on you?” he asks me. “But if your home still respects you, they’ll always be there. So I appreciate him coming back here.”

The coach—who has worked at the school for forty-one years and has a wall inscribed with his wisdoms called “Life According to Fairfax”—considers all the Arts High kids his kids, including the cynosure on set. He tells me that at one point, Jordan was one of the best players in the state and averaged twenty-four points per game. Trust, twenty-four points per game is a prime scoring average at any level. I tease Coach Fairfax that Jordan’s jumper looked a little rusty in the gym. And he says, “Did you see me walk over there and whisper to him? I told him to bend his knees. And you saw what happened after that.”

While MBJ shoots, Coach gets a call from his daughter. “Oh, yeah. I’m with him right now,” the coach says, and with a certain self-possession glides onto the court and slaps the phone into MBJ’s hand. Jordan sounds delighted to hear from her, and they talk long enough to convince me he ain’t rushing off the call.

There’s busy, and then there’s too busy for your people, and the latter he is not.

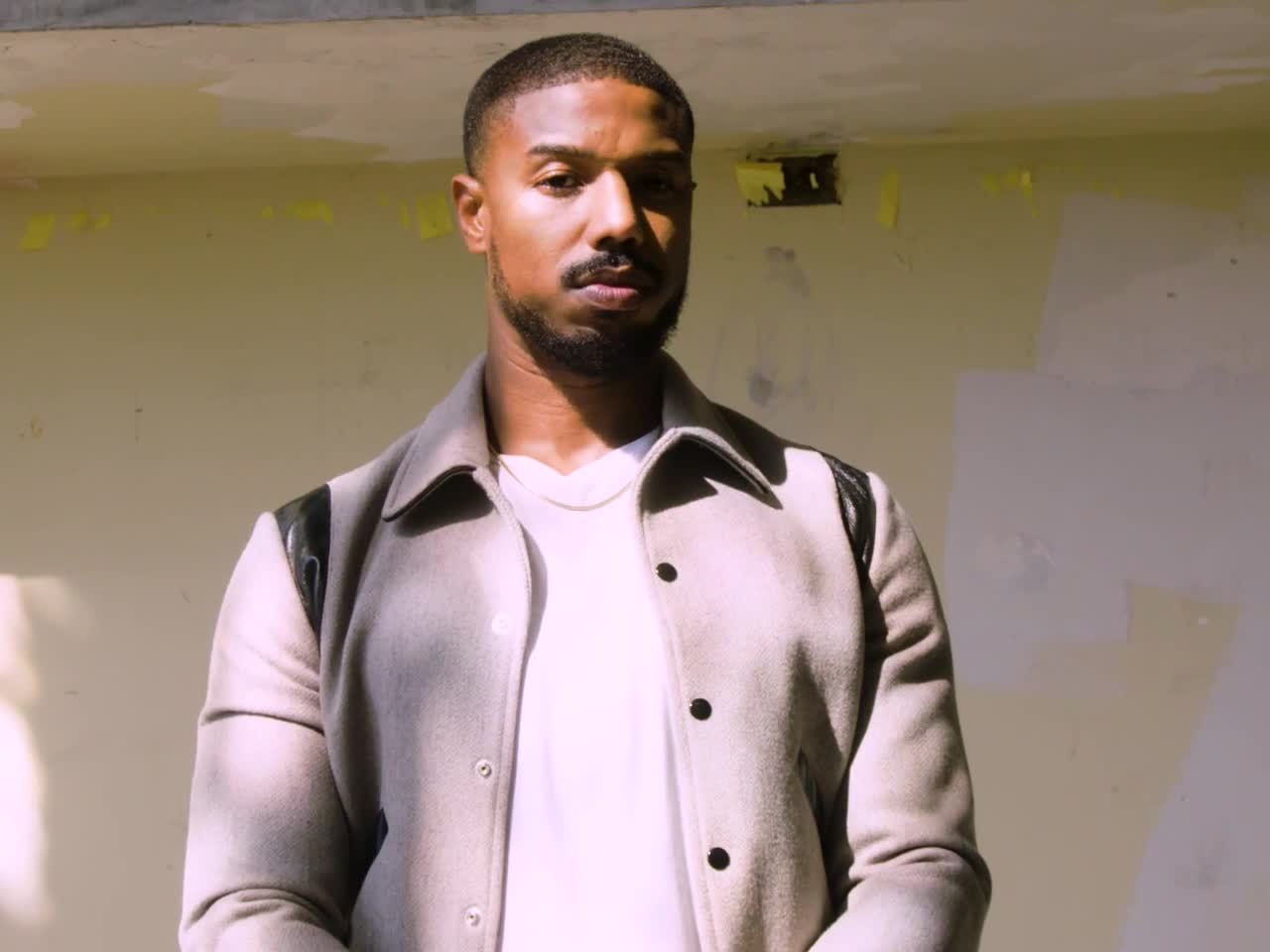

The High Line is a once-abandoned rail track on the West Side of Manhattan—and, that evening, the venue for the Coach 1941 (’41 being the year of the brand’s founding) Spring/Summer 2020 fashion show. (MBJ was named the brand’s first Global Face of men’s wear in September 2018, and this past October released a capsule collection of his own designs inspired by the Japanese manga series Naruto.) The show’s chic set featured bleacher seating, fuchsia-painted floodlights, a stacked configuration of lime-green speakers. Artist Simone Leigh’s giant bronze bust Brick House towered in the center of the space, surrounded by rows of bleacher seats on all sides. In one of those front rows sat British Vogue editor in chief Edward Enninful, and in another, NBA fashionisto P. J. Tucker.

MBJ, aplomb dialed to a zillion, swanked out just minutes before the show began, wearing a light denim jacket with a shearling collar, army-green pants with a black holster strapped to the leg, and combat boots—all from his collection. A phalanx of excited teens he’d invited from Newark Tech High School’s fashion club bopped behind him. MBJ stopped at his front-row seat and posed for pics, smiling fulgent as the floodlights, then sat beside his friend NBA superstar Kyrie Irving and up-and-coming rapper Megan Thee Stallion. The jubilant teens climbed into the bleachers above Jordan.

Soon after, the models runwayed out to Human League’s “The Things That Dreams Are Made Of” wearing leather and prints and tanks and tees and jackets, some of which were the same colors as the speakers and lights. MBJ, hands clasped, watched the models pass. He was attentive, but he’d also mentioned over lunch before the show that he was hoping to make it to Newark later that evening for his great-aunt’s eightieth-birthday party. Tethered though he may be to the world of premieres and after-parties, to fashion shoots and shows, he wasn’t just there representing Coach, fresh to death in his own designs—he was there with a class of high school students he went to the trouble of inviting as his guests, kids who lived just across the Hudson River but umpteen miles away from this bright universe.

No doubt the most excited audience members were those teen invitees, the ones who snapped pictures and turned to one another with I-can’t-believe-this-is-happening faces. It seemed essential Jordan: parlaying his Hollywood status into lending a hand—helping these kids with their future careers, helping the kids at Arts High with an inspiring visit, helping Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative by playing him in a movie, helping the guy he surprise-visited a couple days ago in Newark, a formerly incarcerated man who now runs a nonprofit.

“Everybody can’t be expected to do everything,” says MBJ’s homeboy Coogler. “But everybody got to do something. So it’s the idea of: What part can we play?”

Once the show ended—it lasted less than ten minutes—Jordan rose, posed for a few more photos with his front-row neighbors and his amped-up invitees, and then, with escorts, zip-a-dee-doo-dahed down a narrow passageway, down flights of stairs, and out of sight.

MBJ and the crew head downstairs to the drama department, to a small, windowless room with bare walls and just a few desks. He’s greeted by his old drama teacher Mr. Gonzalez—an affable-looking middle-aged Latinx man with short hair and glasses—and a dozen or so drama students, almost all of them girls. They squeal and grab one another when Jordan stands just inside the threshold.

Mr. Gonzalez grinning beside him, Jordan talks about studying drama in the very same room, about having to memorize monologues. “You might not want to do some of the stuff, but I promise you if you listen to him, he’ll get you ready,” he says. He pledges to return and spend more time, an assurance that makes the girls go even more giddy.

Word of Jordan’s presence has spread, and there are now talks of an impromptu school-wide assembly. This addition to the schedule has got several members of the production team on straight tenterhooks. MBJ’s in a time crunch and will leave right from the school to catch a flight to Berlin and begin working on Without Remorse, a sure-thing blockbuster based on a Tom Clancy book. Crew members usher MBJ back to his trailer for another wardrobe change.

Minutes later, here comes Jordan trooping down a third-floor hallway. The PA system crackles on, and Principal Pedro announces there will indeed be an assembly, and relays instructions. It’s been hot the whole day, and the whole day Jordan has been wearing leather and wool and suffering for it with sweat.

A makeup artist keeps dabbing his forehead. He doesn’t complain.

“I’m low-maintenance. Or try to be,” he’d told me the day before.

In the auditorium, a few hundred students cheer, scream, whoop—oh, I’ve seen a few pep rallies in my day, and this one ranks prime. Teachers, staff, and school security line the back and side walls. From my spot back with school employees, I see dozens of glowing phone screens trained on MBJ, many of their owners standing for a better vantage point. Jordan stands in the center of the stage, wireless mic in hand, a greenscreen behind him. At stage right stand a clutch of adults and the production team’s sound guy, holding a boom mic high above.

Jordan doesn’t talk long and ends with a promise: “I’m on a crazy schedule right now, but I’ll come back and talk to y’all for real and have some one-on-one time with y’all,” and with that he draws the loudest cheers I’d heard any place I saw him over the four days.

We met on a sunny midday in midtown. MBJ was casual in a T-shirt, jeans, and sneakers. A chipper host escorted us to a table in the back corner of the restaurant. Jordan ordered a salad and a tea with honey, lemon, and cayenne pepper. As it turns out, Piaget had hosted a party for him the night before, during which he smoked one too many cigars with Jamie Foxx et al., and that afternoon his voice was paying the ransom.

Hearing of his night made me think of old Hollywood.

Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, Harry Belafonte, Dick Gregory, Sidney Poitier, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee. . . There’s a long and storied history of black actors who’ve also been champions of civil rights, which is to say justice. While one could argue Hollywood—and America—has made strides (imagine, in 1964, when Sidney Poitier won his Best Actor Oscar, he still couldn’t buy a burger where he damn well pleased in a place like Mobile, Alabama; riddle me the state where, tomorrow, MBJ’s safety would be assured no matter which cop stopped his car?), there is still much, much work to be done. Jordan is proving to be one of a new generation of actors committed to continuing the necessary work. And the more powerful he becomes, the more change he can catalyze.

As I see it, there are essentials for becoming, in addition to an A-list actor, an elite Hollywood power broker capable of driving change, not the least of which is having a plan. MBJ told me his plan includes having thriving production and brand-consulting companies and, for the next four or five years, “being in work mode” in front of the camera and directing and/or producing a project or two. He said that further down the road, he’d take a step back from acting and do a movie every year or two, one he “really, really, really” cared about.

Other parts of that plan have been in effect. MBJ’s production company, Outlier Society, made headlines last year when he announced a diversity-and-inclusion policy for all its projects. Later in the year, WarnerMedia announced it was partnering with him to adopt an inclusion rider for all its properties (Warner Bros. and HBO included). Just Mercy

is the first project under this new initiative.

The film is also groundbreaking in that it’s the first to include direct action in its marketing plan, working with NGOs to actually change criminal-justice policy. “It’s the largest campaign ever around the global release of a film,” says one of the producers, Scott Budnick, who is also a criminal-justice-

reform advocate.

MBJ prepared his tea concoction. His hands were the hands of a well-kempt workingman: thick fingers, ashen on a knuckle or two, the nails trimmed but not primped fastidious. He sipped his medicine but didn’t so much as touch one leaf of his salad, and I forsook my burger in solidarity.

Word is MBJ will make his directorial debut on Creed III. He seemed surprised when I mentioned it and didn’t confirm the news. He made it clear, though, that he’d be ready: “I’ve been learning since I was like twelve years old, being on set. Seeing what everybody does, all the departments. From the wardrobe stuff to the sound. I’ve always cared about what everybody needed. It’s kinda like a perfect perspective to have to be able to help run a set. I just love to collaborate. And empower people to do what they do best.”

I asked him if Oscars and box-office numbers would be the metric of his success as a director, if they’d be how he measured greatness as an actor.

Jordan fiddled with the lemon on his saucer. “I’m an athlete, and I compete,” he said, then looked up at me. “So I have to force myself almost not to look at what I do in a naturally competitive way. Because it’s not that the best record wins; it’s not that you’re the greatest player clearly because of the stats. That’s not why you’re gonna get this or that achievement. We don’t operate on that. Ticket sales, awards, that level of success is always a dice roll based upon marketing and so many things that are outside my personal control. And that’s a bet I ain’t willing to take. I won’t bet my emotional currency on that.”

He looked off at something over my shoulder, considering, it seemed, what would be his measure.

“I’ve always wanted respect from my peers,” he said, “to be somebody that will be respected forever, who has an amazing body of work, who affected these kids and these people. That’s my greatness. It’s my scope and my reach. My greatness I want measured by the people that I put on. Like, actor X ten years from now, he has a career that has far exceeded mine. And ask him, ‘Who looked out?’ And he’ll say me.”

The last shoot of the day is in front of the school. A few students who’ve now been dismissed hang across the street, watching the crew set up, their circumspection turning to ogling when Jordan slugs out the front door. School security guards stand at each side of the front steps, redirecting passersby while Jordan has his picture taken for the millionth time today. It’s warm outside. Cars slow as they pass. You can see drivers stop and crane their necks. Someone rolls by with their window lowered and shouts MBJ’s name. Someone else pulls to the side of the road and asks a security guard, “Is that Michael B. Jordan?” in disbelief. The guard affirms it is, smirks as though the knowledge alone affords him some new status. The driver, a woman, waits, waits, and then pulls away.

A man walking his daughter home from school yells at Jordan from the street. Jordan looks up, bolts down the steps, and daps the man—hug included. They talk for a bit, catching up on people they know in common.

This is what it means to be home, that there’s no place like it for those who ain’t forgot it.

On the ride to Newark Penn Station, I watch the city scroll past my window, mostly tall buildings made of brown bricks, and colorful storefront signs, and wide avenues, and I think of MBJ and a black car loaded with his team zoom, zoom, zooming to make his Berlin flight, think of how exhausted he must be but how he wouldn’t wish it otherwise.

For fact, I’m under no illusions that MBJ and I are fast friends. The truth is, we won’t be exchanging texts or sending each other holiday cards. There are odds about none we’ll run into each other months or years from now and fill each other in on lost time. And yet I feel a kinship with the man. Indeed, he’s an A-list global megamoviestar, but he’s also my brother, kindred because, among other reasons, he us up there on that screen, portraying our tragedies and triumphs, living superhuman and human and all the while saying, Look,saying, Look again, asking, Do you see us?

There’s a scene in Just Mercy—which MBJ produced in addition to starring in it, the point being he really wanted this movie out in the world—where the Jamie Foxx character (the man condemned to death over a false conviction) asks Bryan Stevenson, the lawyer, why he’s trying to help when no one is paying him and the chance of success is so small.

Jordan-as-Stevenson says, “I know what it’s like to be in the shadows.”

Here let me go on record as one who holds great faith that when Michael B. Jordan jets off to Berlin and wherever else, that when he mounts another festival stage looking super swagfabulous or wanders another Hollywood shindig with the earpiece dudes in tow or perches front-row for a fashion show or poses for a cover shoot for another magazine, the plight of the disfavored won’t be far from his mind, and he will be plotting all the while more ways to use his limelight to illume those who exist in the shadows, a place where I once dwelled, where far too many exist still.