Shirley Blackwell's death was completely ordinary. She died on the day after Christmas 2020, at the age of 70, after long term kidney and lung issues. The event was reported in the local paper in Alliance, Ohio, dispassionately listing the usual things that are printed when a beloved member of a community dies: where she worked, who she is survived by, and details about where the celebration of her life would be held. Nothing was mentioned about the infamous pictures that she appeared in as part of a series for Life magazine, an event that would alter the course of her family forever. Nothing was said about the struggle she had faced for years trying to find money for college. And nothing certainly was mentioned about the time her mother’s dreams were put on hold after being fired from her job for participating in the magazine spread. Instead, niceties appeared in her small hometown paper and the death of the little girl in her Sunday best standing alongside her aunt outside of a “Colored Only” entrance in 1956 was ignored by the national media.

Perhaps it was ironic that Shirley’s death was overlooked by a world that never seemed to know or care much about her life but was willing to use her image over and over to exemplify an America that once was (and one that many would argue still is). Perhaps that was the cruel joke about it all—the pictures which ended up causing her family so much pain reflected the notion that many have come to understand about Black people in America: we are often seen but unseen.

If you have watched any sort of television or films about Black life in the past few years it would be hard to miss a six-year-old Shirley, standing alongside her aunt outside the Saenger Theatre in Mobile, Alabama. Unlike so many of the black and white photos of the civil rights era, the colorful collection emphasized family, hope, joy, frustration and perhaps an ordinariness to the experience of segregation, giving depth and nuance to the issue beyond just pain and tragedy. The subjects were portrayed not as victims of an unjust system, which they certainly were, but survivors, even thrivers, in a world that had constantly shunned them. The pictures were not just about Shirley and her Aunt Joanne, but about their extended upwardly mobile clan—the Thornton family—and the progress they had made as descendants of slaves.

The photos from the series have been increasingly popular as America once again tries to work out its shit about race and Blackness, appearing in shows like Lovecraft Country, the Sex and the City reboot And Just Like That..., HBO’s adaptation of Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me, and in films like I am Not Your Negro. Yet the story behind these beautiful color photos and the trouble they caused one of their subjects is less known. After finding letters from Shirley and her mother Allie Lee to Life Magazine in an archive at the New York Historical Society about the toll the series had on their lives, it became clear that it was long overdue for their story and the dreams they once had, to be told.

Allie’s frustration as she pleaded to a magazine who never quite seemed to understand what she had lost, felt personal to me as a Black woman. For a while I wanted to keep these letters, which have been publicly available but never seemed to spark the interest of others, a secret. I wanted the pain and frustration of yet another Black woman with broken dreams hidden from the world. But as I emailed the first letter that Allie wrote to Life magazine to her great-nephew, Michael Wilson, who had no idea of his aunt’s correspondence with the magazine, in the shadow of worldwide protests over the unnecessary death of George Floyd and another alleged American racial “reckoning,” it seemed as if Allie Lee’s quiet story of protest was timelier than ever.

As a child growing up in the sixties Michael Wilson had always heard murmurs and whispers about the book, yet he never quite knew what anyone was talking about. It wasn’t clear what the book was or why it was important, but he knew one thing: the book meant pain for his family. He knew its contents angered some white people and caused his Aunt Allie Lee to flee the South and give up the career that she had worked so hard to attain. He knew that she had been sad after the publication, but the rest remained a mystery.

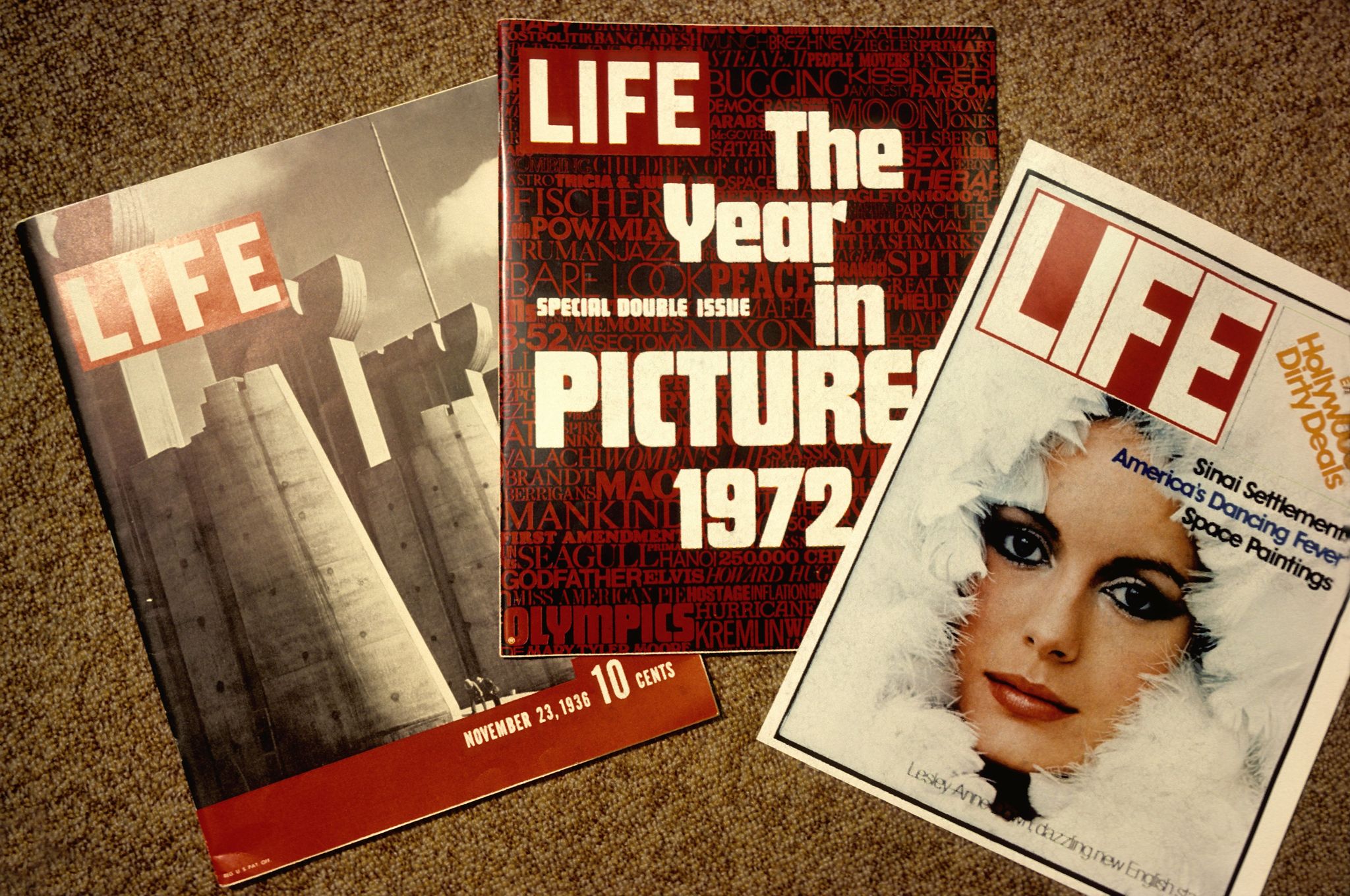

It wasn’t until Michael was in college that he started putting the pieces of the puzzle together. First, he came to realize that the book was not an actual book, but a magazine, Life magazine, and it contained a series of articles and photos documenting the experience his family had around segregation in the South and how they dealt with the “restraints” placed upon them.

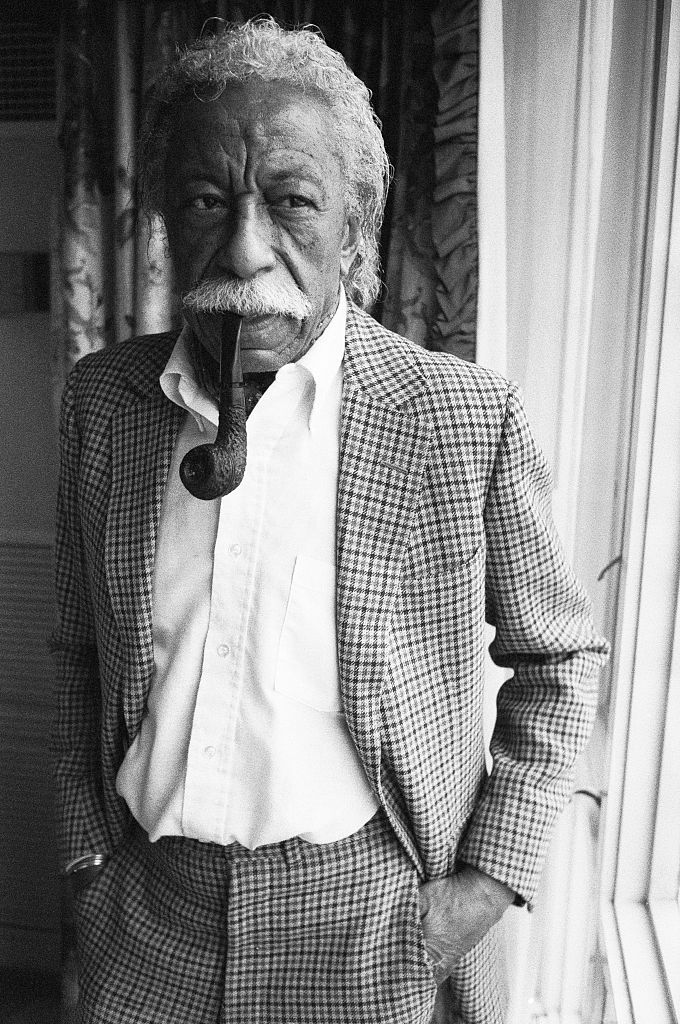

The series drew some ire when it was originally published, inspiring shock and rage from the usual chorus of liberal whites in the North, but then largely fell into obscurity. Even many of the photographs taken for the story were lost until recently, despite being part of legendary photographer Gordon Parks’s catalog.

The fourth installment of Life’s five-part series titled, “Background of Segregation” is The Restraints: Open and Hidden. It was written by Robert Wallace, a white staffer at the magazine, though Sam Yette, an uncredited Black freelancer, seems to have done a fair amount of the reporting. The article is largely patronizing and paternalistic and much of it is forgettable (for example, Wallace seemed to believe the matter of segregation was a matter of “feeling,” inconvenience and lack of access to the white world rather than about danger and economic inequality). Parks’s boldly colored photographs and Yette’s account of one Black family’s story of progress strike an entirely different tone. Parks's pictures told another more complex story, one where Black people were dignified, unafraid, and committed to work and family. Rather than highlight protest and pain, Parks’s photos show Black people doing ordinary things: a grandfather taking his grandchildren for a walk, a Sunday service at a Baptist church, and children playing in the rain. There are women in their Sunday finest, drinking from water fountains, families getting ice cream, men at work, and Black kids with dolls, telling the story of a family that was surviving, sometimes even thriving, in the face of adversity.

There was a section on the married elders Albert and Ondria Thornton. Another on Virgie Lee Tanner and her family, whose husband was a mechanic at an air force base and another about a successful college professor E. J. Thornton. While the pictures of the Thorntons were a contrast to the stereotypical images of mammies and pickaninnies often displayed in the mainstream media about Blacks at the time, it was the story of E.J.'s sister, Allie Lee Causey and her family in Silas, Alabama, that proved how precarious the American dream was for Black families.

The Causeys were shown to be a modest, hardworking upwardly mobile family that were considered high income earners in their community. Allie’s husband Willie was a farmer and a woodcutter who made a living from the 16 acres of cropland and 24 acres of timber he owned with the help of his sons. Allie Lee earned $2,500 a year as a teacher and helped Willie out with his business and five of his children while raising her daughter, Shirley from a previous marriage. She was known to speak up for what she believed was right. She organized voting drives and taught other Black people in her community the Bill of Rights, a requirement for voting in many Southern states. Together, the article noted with more than a hint of condescension, the family was so comfortable, that Willie bought a Chevrolet the previous year as a symbol of their success and “equality” which Wallace seemed to deliberately leave in quotes.

Images of Allie Lee’s run down classroom and Willie working with his sons peppered the profile of the hard-working family along with Allie Lee’s frank rumination on the “restraints” on Black people in Alabama and her hope that it would all end soon. “Integration is the only way through which Negroes will receive justice. We cannot get it as a separate people. If we can get justice on our jobs and equal pay, then we’ll be able to afford better homes and a good education,” she said to Yette.

No one thought much of Allie Lee’s statement or Parks’s images after the article was published in the September 24th issue of Life. But by October 1, Allie was suspended from school, Willie’s truck was confiscated, and white business owners refused to work with him anymore.

On October 2, 1956, E. J. Thornton sent a letter to the editors at Life magazine praising the segregation series for its authenticity and accurate portrayal of Black life in the South. “We were proud that we were able to be used to present a picture of the Negro and his plight in the South,” he wrote, before attaching a letter from his sister Allie, who had asked him for help upon publication of the series. He acknowledged that Life probably could not do much except make public “the repercussion of the story” but passed on his sister's frustration. “We are having it tough here in Silas,” she wrote. “Mr. Willie’s job is being boycotted and no one want to give him gas, nor food, sell him anything asked him to leave threaten his life. My job is threaten (sic) of being taken away from me. I don’t know what to do…these people are very very mad.”

Life sent Dick Stolley, a white reporter from their Atlanta bureau to report on the fallout. He found out that the white people in Silas were in an uproar because Allie Lee mentioned the word “integration” and “justice” in the story. When members of the Board of Education pressed the teacher, she said “those are not my exact words” but failed to disclose her exact statement. She told Stolley that she talked in depth with Yette about segregation but asked him not to“put anything in the papers that will hurt us.” Still, she emphasized that she was not misquoted and doubled down on her belief in “integration and justice for Negroes.”

The reporter found that there were some inconsistencies in the reporting, for example Willie did not own his truck and saw (they were mortgaged) and there was an error about Willie’s business earnings but Stolley said he believed Willie’s grave offense was that he thought he was a “first class citizen,” able to own a truck and be a lumber dealer when the white community saw him differently, “He had to go. . . . He had been ungrateful. He had talked of discrimination,” he wrote in a memo to his editors on October 11th.

The white community where they lived was shocked that a national magazine would profile a Black family and appalled Allie spoke so freely about the problem of segregation, leaving to Stolley to believe that ultimately the white people were bothered by the Causey's dare to dream: “The Causey’s didn’t do anything wrong except to show bad judgement in what they said, not realizing the neighbors would be reading it in black and white. They also owed some money, but that is not a crime, and their creditors have been making profits from the Causey’s for many years,” he noted in the same memo. The Black people in the county found nothing wrong with the story, but danger lingered in the air.

Allie Lee thought about begging for her job back but said it was unclear if that is what the school wanted. As the family remembered an uncle of Allie’s that was murdered by white men in the area and knowing what happened to Black people perceived as being “uppity,” the terrified family did the only thing they could: wait.

Later, Allie Lee claimed she did not know her words to Yette about segregation were going to be published but continued not to renounce them. Stolley said there were some inconsistencies told by Allie Lee after the story was published in the name of self-preservation, but he was sympathetic to the dilemma the family faced. The reality was the truth did not matter in Silas, anyway. Bloodshed seemed imminent. The family was warned violence may fall upon them and Willie believed they would be killed, so within days they packed up and left for Mobile.

According to Life’s reporting and letters from Allie, the magazine found out that after moving, Allie Lee wanted a divorce. She said Willie was abusive and repeatedly hit her and threatened her with a gun. She said their relationship was bad before the story and became even more hostile after publication, as Willie blamed her for all their problems.

Due to the nature of their troubles, Life decided to give both Willie and Allie a lump sum.

Allie Lee received what would be a year’s pay and Willie received $1,000 to buy a new truck. Life also ran a follow-up story about the boycott against the Causey family in Silas, written by Stolley on December 10, 1956. In it, one white person noted, “People in the north don’t understand what we’re up against down here… Talk about restraints… if he thinks he had restraints before, I’d like to know what he thinks he got now. It’s the burr heads like him that are causing us trouble. We ought to ship every one of them back to Africa.” Life never reported on the family again in the pages of the magazine but their correspondence with Allie, and involvement in hers and Shirley's lives, played out over the next twenty years.

By August 2, 1957, Allie was out of money due to paying off debts, helping her parents, and looking for work. She was planning a move north to Alliance, Ohio, where she said she could do housework for $6 or $7 a day, more than a domestic in the South. She informed the editors at Life she had met with renowned lawyer Thurgood Marshall, who suggested that her wrongful termination case against the Choctaw County School District be dealt with by the NAACP, but that suit never seemed to materialize. In March of 1958, Stolley told Deputy Managing Editor Robert Elson that Life had sent Allie Lee $300 dollars a few months ago with some “strong-worded advice” that she find a “steady job.” The next month, Stolley wrote to Allie Lee suggesting that she “develop some skills besides teaching” until she could find a full-time teaching job. He also told her, in a somewhat patronizing way, that he was sure she wanted to take care of herself and Shirley without, “relying on anybody else,” since it was also what he wanted and what his editors in New York “expect.” He included a $150 check.

Life eventually gave Allie Lee money for secretarial school, hoping that it would help her become a typist, but she continued to want to pursue teaching. When she had trouble passing the typing test, the editors at Life became concerned about her narrow focus on teaching: “Her life is centered on being a rural negro school teacher. This she can never be again. She seems unable to cope with the new life she has been in now for more than two and a half years… as long as she and her family know we are standing ready with checkbook in hand, I’m afraid she’ll never solve her own problem” wrote Stolley in a letter to Elson on March 5, 1959.

Parks seemed to be marginally aware of the situation, but uninvolved. Allie continued to write to the editors over the next decade, still frustrated that she wasn’t able to turn things around. On August 30, 1961, Stolley wrote another memo about Allie Lee’s plight: “Allie Lee was almost 30 when she completed college, and she stuck with it only because of her determination to teach school. So, quite naturally, her first thought was to teach in Mobile. She had little luck, even in substitute teaching. Her education wasn’t the best; and it’s entirely possible the Mobile school system knew about the trouble she had been in.” Stolley estimated they had given Allie only $1,000 to $1,500 over 5 years since the move from Mobile; but the editor continued to feel bad about the fallout from the article: “The worst part of this tragic situation is that Mrs. Causey had to leave a comfortable teaching job she undoubtedly could have had for the rest of her life. She was fulfilling a lifelong ambition in that job...She was a good teacher, too, but the education and training that was good enough for a Negro school in rural Alabama was not, I’m afraid sufficient for Mobile. This is the root of the problem,” he noted in a letter to General Manager Arthur Keylor.

By 1962, she had moved to Alliance, Ohio, and reunited with her first husband, (Willie divorced her that year) Edward, and became known as Allie Lee Kirksey. Marriage did not ease Allie Lee’s troubles and she continued to write to the magazine about her “difficult time.” In December of 1962, a magazine representative went to Alliance to assess her situation. They wrote out another long memo claiming that Allie’s financial difficulties were not as bad as she had suggested and were primarily the result of her husband’s drinking habit. Her husband, the report found, worked for American Steel, and made a decent salary taking home between $123 and $127 for two weeks’ worth of work, but a gambling habit curtailed the family’s progress. Her only real need for steady employment, the memo glibly said, was so that “she could be financially independent of Edward Kirksey, her husband,” as if wanting to not rely on a man was a flawed trait.

When she could, Allie worked as a substitute earning $16 a day, but that, she said, was hardly enough to survive. In the South, she said, she made less but the income was steady. Life tried to appeal to the Ohio school district, but soon learned teachers and principals had complained about Allie because they believed her bad grammar, poor writing and speaking skills and her threats to hit ill-behaved kids in the classroom (something that may have not been so unusual at the time) did not make her fit for teaching. Life sent her $100 the following month.

By July of 1963, the editors at Life sent Allie Lee a letter stating they could no longer help her. Her receipt of the letter resulted in anger and desperation, and she now wrote more about her troubles growing up: Typhoid fever, bad work, a long walk to school, and being forced to sleep with the landlord for money. On April 11, 1966, she wrote to Gordon Parks, “I have been mistreated and forgotten by Life magazine and the white people of Alabama. I know if the story had not been written I am sure I would have not been suspended. What good did it do to help in the dirty heart of the white of Choctaw County? I have been made to make a living by any way I can. The North is just as bad as the South. Both are a sin. I rather see the dirt in the opening then to find it under the rug. Which would you rather sting you a bee in the open or one under a leaf? Both will sting and both will hurt.” She wrote her belief that her southern accent and age (she was now over 35) negatively impacted her ability to find a job and she was relegated to cleaning floors. “I have been forgotten by all.”

She also wrote the editors at Life that year, claiming Parks and Yette were trying to make money off her story and demanded Life pay her for lost wages: “He and Gorton Park (sic) were trying to make a million dollars any way they could.” Stolley responded that Life had given her about $5,000 and owed her nothing else. However, when Allie Lee wrote again in 1968, a few months after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, asking for help for her daughter Shirley, they conceded.

Shirley had been admitted to the University of Toledo following her high school graduation but did not have the money to attend. Before Life decided how to help her, Shirley, now seventeen and seemingly influenced by the burgeoning Black Power movement, sent a letter to the Time and Life chairman of the board, bluntly invoking racism at the publication and showing a bolder stance that differed from her mother “I’m not like my mother,” she wrote in September 1968, “she believes that God will work it out . . . but we need a change now. . . . The new Black generation will not—and doesn't plan on taking what the older generation did. If it wasn’t for your magazine my mother would have a job.. . . . After writing to you for help, this is what we got, (Cogradulation (sic) on your daughter graduation) dam the congradulation (sic). We need help and I want it now, not tomorrow next year but now. . . . It is plan [plain] to see that life is a racist, they don’t care what happens to the Black family that they destroyed 12 years ago . . . I am going to school one way or the other even if I have to wrote my past 12 years living in hell, how Life destroyed us and forgot all about us, how they turn their backs on the little Blacks.”

Life decided to pay her tuition starting the fall of 1968, noting that while the letters of Allie Lee had “become more rambling, less coherent, and sad,” her main concern was often for Shirley. They had not, on the advice of legal counsel, responded to her letters, but said they were trying to do everything possible as an organization to help young Black people. An internal memo written by Ruth Fowler, the assistant to the publisher, said that by aiding the family again they were “perhaps acting foolishly from a legal point of view.” Stolley was pleased (perhaps a little too pleased, I believe) at how the “sad episode” was resolved, stating how proud he was about Life’s assistance to Allie Lee. “I figured that no matter how ugly she got (uppity isn’t the word, in this case), she would continue to be treated fairly,” he replied to Ruth.

By the start of 1969 Allie Lee had written to Parks telling him she was unhappy, had a poor Christmas, and needed some more help. Parks was shooting his first feature-length film but wrote to photo director Richard Pollard asking if Life could give some assistance to his former subject: “This woman has been writing to me about her condition for quite some time. Would you please have someone look into this and see if she is as badly off as she claims…I don’t know if anything can be done, but it is bothering me and I wish Life could in some way clarify their position.”

Ruth followed up with Parks’s request noting that Allie was a “fine person” though “low on the list” to teach in Alliance. She informed Parks and others that an anonymous scholarship of $2,500 would be donated each semester towards Shirley’s tuition, board, and living expenses at the University of Toledo. Finally, it seemed like things were finally looking up for Allie Lee and now Shirley.

But that year another memo from Ruth revealed how annoyed and disappointed she was with the Kirksey family. Allie, she believed, was still caught up on being a teacher and had only been able to maintain part-time employment and Shirley had decided to only take three courses in school-getting a D in one and failing the other two.

As I read this, I was frustrated, both at the editors inability to see how dramatically Allie’s life dream changed because of the story they published, but also at Allie for failing to find work—and Shirley for not getting straight A’s. I admit, my latter qualm was probably unfair. As white editors living in the North, they just didn’t quite get Allie’s sacrifice and how hard it had been for her to even act on her initial dream, how much it had meant for a Black woman to become a teacher, when everything around her told her she was less than. And then to have it snatched away? I could understand why she was so devastated and her life so destroyed. At the same time while I understood Allie Lee’s plight in a Jim Crow world, I continuously wanted her to finally catch a break, to find success in another field or for Shirley to have the perfect report card. But those kind of wishes are often the territory of fairytales, or some Black respectability fantasy, distant from the reality of inequality, poverty, white supremacy and racism. So, I pushed my own questions aside and kept reading.

Allie Lee continued to express despair. In November, 1970 she wrote to the editors again demanding 14 years’ worth of pay, while again writing just how bad her situation was in a postscript. “Today I don’t have food. I don't have bill money. I don’t have anything.” The next year, she was more frustrated than ever. “No one will help you when you are poor not even your own race. The white people cause me to be without a job.” She tells the magazine she is desperately in need of assistance since she can’t get work and is “very poor.” In a memo that same year Ruth seemed to continue to be irritated by Allie Lee, “We offered her all kinds of training choices over the years, but all she ever wanted to do was teach and she has refused or abandoned all other prospects… Life and Time Inc. have been very generous to Allie Lee, but she again now, continues to write pathetic and demanding letters... She is, however, not in desperate need… and her daughter’s education is covered,” Ruth wrote, noting that the publications’ “liability is not an actual one we wish to acknowledge, but a moral one we have assumed.”

Allie’s letters continue: she has been removed from the substitute teaching list, has a heart condition, bad teeth, and has been relegated to cleaning floors.

Soon more bad news came. After spending two complete semesters of college and a few part-time semesters, Shirley dropped out. On December 27, 1972, Life, having sent $9,150 for Shirley’s dream, seems to have closed the case on Allie Lee and Shirley.

In an undated letter, Allie Lee sent a note thanking Life. She said it was hard for Shirley to finish her schooling due to her “southern half day education” but she would try again soon. She also noted Shirley was also looking for work, which was hard to find. On May 15, 1974, in what appears to be a final letter to Life, Allie Lee wrote of her disgust for the magazine and Samuel Yette because he did not “place the exact words.” “I lost four years of college work where I wanted to help children, lost My Retirement and I have worried myself down. I hate Life.”

Allie Lee’s story of course does not end with her correspondence to Life. She went to live thirty more years until the age of 90, passing away in 2006, still in Ohio. Shirley got an Associate’s degree from Stark State, raised two sons Michael and Brandon, and enjoyed spending time with her six grandkids who all still live in Alliance. She didn’t talk much about the series that caused her mother so much despair.

In the end, Allie’s dream of teaching again was never fulfilled and she never went back to the South where much of her family resided. Most importantly, as the letters to Life reveal, never again did she seem as happy as she was when she was teaching. Her nephew Michael Wilson, who lives in Mobile and serves as the family historian, tells of the change.

“She became this real serious woman,” he told me last fall. “It just broke her down because she was never able to teach again. And that's all she wanted to do was to teach.” Still, even though her life was never the same, Wilson said she was ultimately glad that she spoke up and remained to be a “determined woman.” “I know my aunt did not regret one minute of it. That was the sacrifice that she wanted to make.”

Though the stories of other families that Life assisted have become more well known, like that of the Fontenelle family in Harlem or the young Brazilian boy Flavio da Silva, Allie Lee and Shirley's story is rarely told. Bill Hooper, an archivist that has been curating the Time Life archives for over 40 years, speculated that unlike some of the other stories, the plight of the Causey family was never really told because it was not a “happy ending for all.” Parks wrote about the challenges he faced in shooting the series, but it’s unclear how long he kept in touch with Allie. In reflecting about his impact on Flavio’s life he wrote, “As a photojournalist I have on occasion done stories that have seriously altered human lives,” he wrote in the seventies. “In hindsight, I sometimes wonder if it might not have been wiser to have left those lives untouched.” I wonder if he felt the same about the Causey family.

In 2012, negatives of the segregation series were found by the Gordon Parks Foundation in the bottom of a box in their archives (only 26 of over 200 photos Parks took were published in the magazine), including the one of Shirley with her aunt standing underneath the coloreds only sign. They were published, made part of an exhibit and soon started appearing everywhere. Shirley’s photo with her aunt underneath the “coloreds only” sign has probably eclipsed the other photos of Allie Lee in the public memory, but Allie Lee’s sacrifice and her hope for a better world also warrants attention.

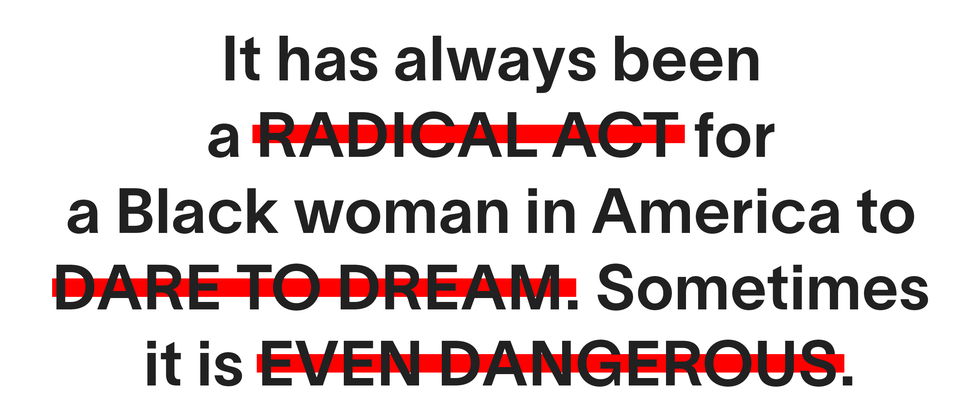

It has always been a radical act for a Black woman in America to dare to dream. Sometimes it is even dangerous. In Alabama during the mid-fifties, both those things rang true as Allie Lee Causey decided to tell the world about her dream of a better life. For even uttering the hope of a better future Allie Lee’s dreams were killed, and suddenly her beloved career and the life she had, perhaps the best life she could have had as a Black woman in rural Alabama, was gone. But that does not mean her life was in vain.

Michael’s family now talks more openly about the photo series that his family was a part of, and he is proud of the stand his aunt took for that once mysterious book. While he knew nothing of the letters she had written to Life, he already understood the sacrifice that she had made and failed to believe Allie’s life was unfulfilled. “She didn't have nothing. She had a hard time, you know, she was never able to fulfill her dream of being a teacher,” but he said, because she stuck to her values, “she was free.” Perhaps for a Black woman in America, that is the biggest dream of all.

This article was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.