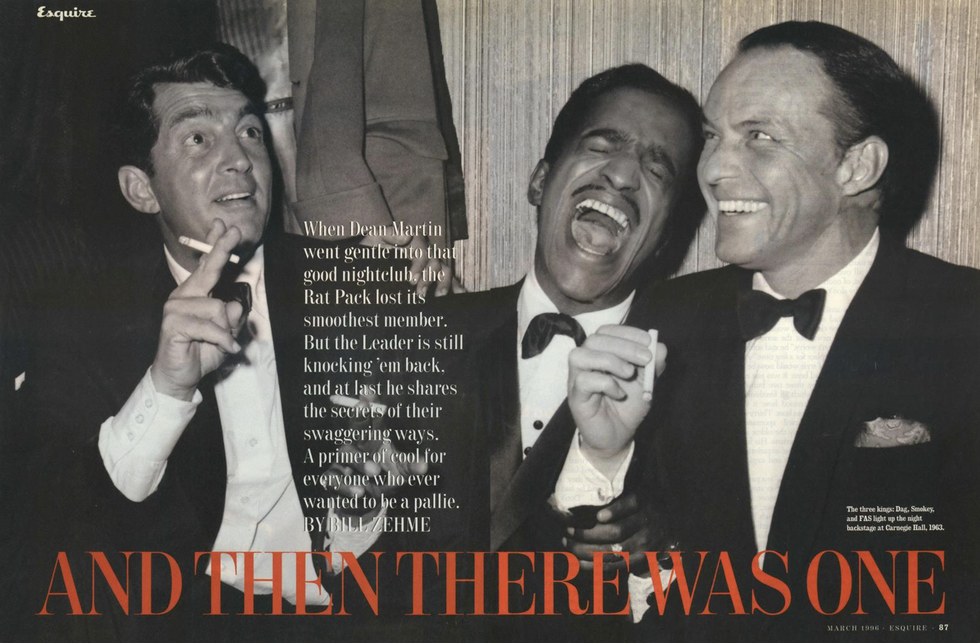

Bill Zehme, who wrote soulful and hilarious magazine profiles of show-business personalities from the ’80s through the aughts, turning a tired formula into something vastly smarter and more insightful, died last weekend in Chicago after a ten-year battle with cancer. And now, so as to make us laugh, what would Zehme do but quote his idol Frank Sinatra? “You’ve got to love livin’, baby!” Sinatra told him for his classic 1996 Esquire profile, “because dyin’ is a pain in the ass!”

Zehme made his mark with comic portraits of celebrities, chiefly for Rolling Stone and Esquire but also for Vanity Fair and Playboy. Chicago was his home but Hollywood his canvas. When reached for comment on Zehme’s death, the writer and director Cameron Crowe, who began his career at Rolling Stone, said: “The world feels a little less swinging” without Zehme. “You ask why his pieces felt different—he knew how to swing.”

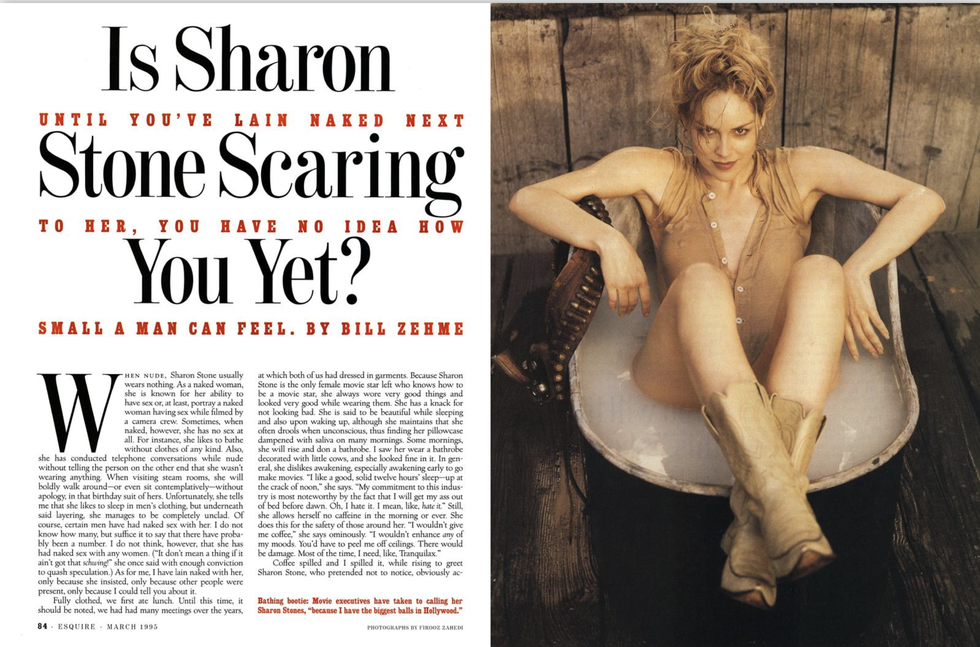

And he attacked his craft like an anthropologist of the famous. It was no chore for him to hang around Tom Hanks or Regis Philbin or Barry Manilow. He wrote about Sharon Stone three times, and even got naked with her once.

“It’s hard to explain how one can miss a journalist so much,” Stone says. “Bill was a wonderful person, a delicate, delicious, open, deep, robust feast of a human. Bigger and more special than most. A holiday of a man, the kind that comes around very rarely, that you remember forever, like the Christmas you got the things you thought your parents couldn’t afford.”

Zehme took very seriously what a lot of people saw as a superficial pursuit (without ever taking himself seriously). Celebrity profiles don’t win you respect in literary circles, that’s for sure. “The celebrity interview is the lowest form of journalism,” legendary film critic Rex Reed, who during the late ’60s became famous himself as a celebrity interviewer, told the Chicago Tribune in 1986. “It’s such hard work—to take these boring people and make them interesting.”

With all due respect to Reed, he’s wrong about “celebrity interviews.” Just because so many people are bad at writing them doesn’t mean the genre is inherently worthless; it means they’re the hardest kinds of pieces to do well. “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” was a celebrity profile, and a lot of people think it’s the best piece of magazine writing ever. We do still read it almost sixty years later, after all. So Gay Talese was a celebrity profiler. And Zehme was like Gay Talese, only funny.

“He was a writer who made things look easy,” says his former Esquire colleague Tom Junod, “like one of those rock ’n’ roll bands that made aspiring guitarists think, I can do that from the refuge of their basements. He was funny without being cruel, generous without being soft, and he saw everything without resorting to judgment—he was approachable, and yet someone to aspire to. But of course, when you did aspire, in print, you found out that you could imitate all his mannerisms and still miss the music, the details he harmonized in those beautiful short sentences which accumulated on the page with cascading forward motion. And you would miss the warmth.”

Though he was six-five, Zehme possessed a self-effacing demeanor and was a natural listener. “He had an uncanny talent for putting his subjects at ease and happy to dump their purse,” says David Hirshey, his first editor at Esquire. “Unlike some other celebrity profilers, Bill didn’t hunt for dirt or skeletons. What interested him were those subtle nuances that revealed character.”

And when it came to suffering for his art, Zehme was also one of a kind. Hirshey remembers hovering expectantly over the fax machine as Zehme blew through another deadline, only to have the pages curl out of the machine, revealing three perfectly crafted paragraphs. Where’s the rest of it?, Hirshey would call and ask.

“Oh, it’s coming,” Zehme would say breezily.

Zehme idolized those mid-century titans of American cool: Frank Sinatra, Johnny Carson, and Hugh Hefner, each of whom he profiled for Esquire. But his real affinity was for the comedians he interviewed—Eddie Murphy, Sandra Bernhard, Jerry Seinfeld, Chris Rock among them—because he was essentially a comedian himself. The longform writer as stand-up.

“Bill was so much fun to talk to because he knew as much about comedy as the comedians he was writing about,” says Albert Brooks. “He had a great sense of humor, was genuinely interested in his subjects to the point of obsession, and was a great guy to spend time with. He will really be missed.”

Zehme possessed the kind of encouraging laugh of which comedians dream. “You knew you were on the money with a premise or a punchline when he laughed,” says Richard Lewis. “I would see his eyes twinkle and then he’d laugh so loud—it was a gunshot laugh, coming back at me with love.”

“He had an outstanding knack to get inside the head of anyone he was interviewing and get from them what nobody else could,” added Lewis. “A lot of that had to do with his genuine love of show business, his curiosity about pop culture, and how people perceive celebrities. He’d dig way deeper and get to the soul of his subjects.”

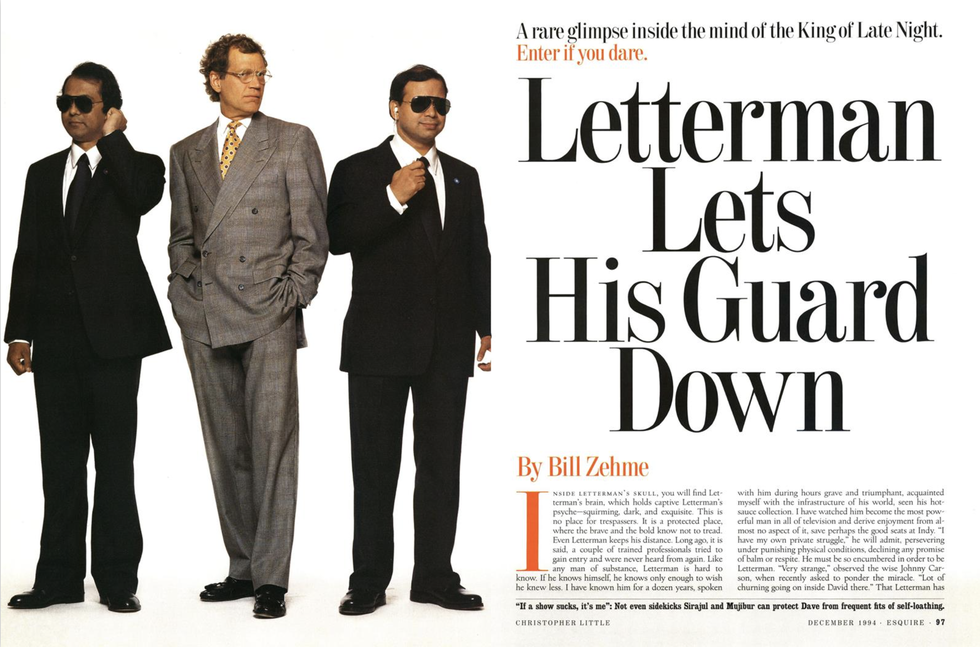

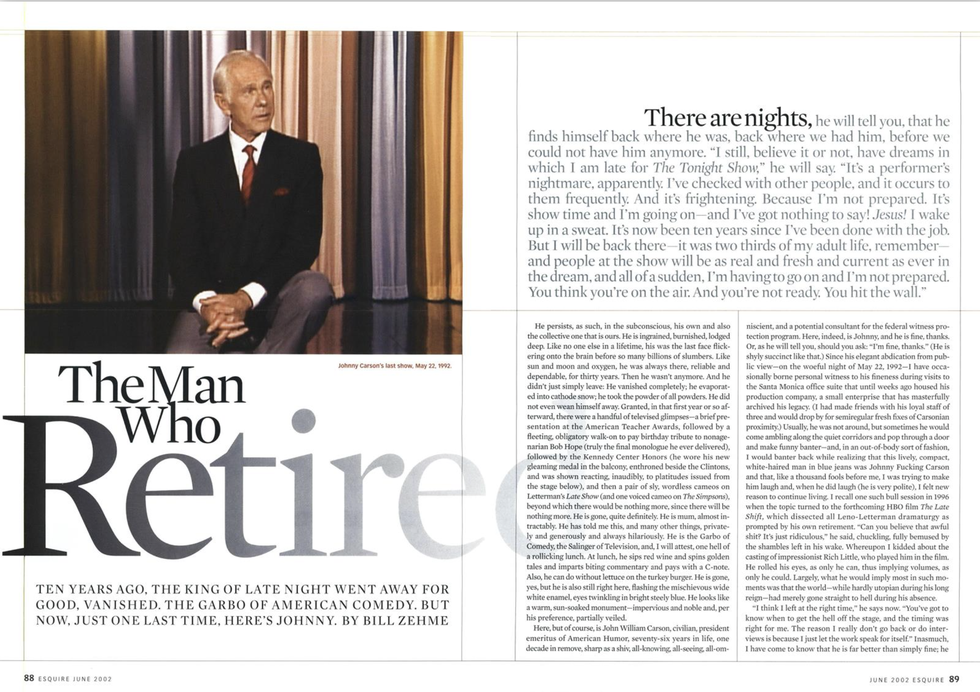

Zehme’s devotion to the gods of late night bordered on the religious, and his chronicles of the talk-show wars between David Letterman and Jay Leno in the ’90s are priceless. He was the only reporter to interview Carson after he left television; Zehme’s 2002 profile “The Man Who Retired” led to a book deal as Carson’s official biographer (a book that due to his illness would never be finished).

“Johnny was never entirely comfortable, ever,” he told me in 2016. “At the same time, he put guests immediately at ease. He didn’t want anybody to be upset or intimidated. Johnny wanted everybody to look great. That’s why he was such a great host, because he wanted everybody in the room to shine.”

Zehme too wanted people to shine. In Chicago, he was a legend. He liked a drink and liked to stay out late. But he quit boozing before the cancer got in the way and robbed him of the strength to finish the Carson project. It would likely have been his masterpiece. Still, he leaves behind a string of memorable books, including The Way You Wear Your Hat, an assemblage of Frank Sinatra wisdom; Lost in the Funhouse, the definitive biography of Andy Kaufman, his best book; and Intimate Strangers, a tidy and satisfying collection of his magazine work.

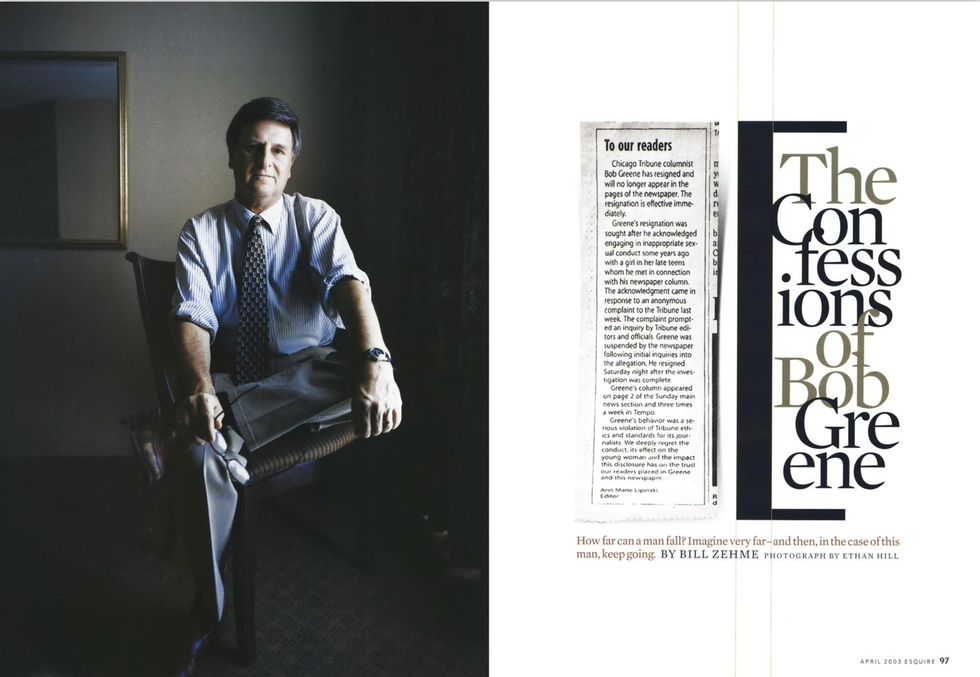

His last great piece of writing could in no way be described as a celebrity profile. “The Confessions of Bob Greene” was about Bill’s fellow Chicagoan, a newspaperman who had made a huge name and career for himself by weaving a wholesome myth of America from the Midwest, one column and best-selling book at a time. His life spun into chaos after a sexual encounter with a girl in her late teens from years earlier came to light, and Greene was promptly fired and shamed. The story was about the free-fall of a prominent man, a person that we thought we knew well but didn’t really know at all, but it was more than that.

As Zehme immersed himself in the story in the immediate aftermath of Greene’s disgrace, Greene’s wife was also dying a terrible death. As Greene kept vigil at her bedside, her suffering compounding his shame. “Bill had always gone deep and demanded a lot of himself to master his subjects,” says Mark Warren, Zehme’s longtime editor at Esquire, who worked with him on the piece, “but this was an entirely different experience for him—his voice would crack and shudder when he talked about it, in calls late at night. The ironic detachment that worked well for dissecting a movie star abandoned him completely, and he was left with nothing but raw feeling and human loss.”

And that’s what that piece ultimately was about: When the myths are stripped away, what are we left with? The story won Zehme the National Magazine Award for feature writing the next year, a recognition that was both long overdue and woefully insufficient. Just as the Oscar never goes to the brilliant comedy, Bill Zehme—genius of an unfairly maligned form, only got his just deserts once he almost literally bled on the page. It was a heartbreaking note to cap a career, a rueful irony that no one would appreciate more than Zehme himself. And maybe the stark departure of his last classic profile—and of course the devastating illness that he would endure—are the best ways to put his endlessly entertaining and delightfully smart body of work in some kind of relief and leave us with a renewed appreciation for the man and writer that was Bill Zehme.

“One thing I have realized through all of this is that you better laugh every day of your life,” he would tell Rick Kogan of the Chicago Tribune, at a time when he didn’t have much to laugh about. So do what the man says and do yourself a favor: Read the enviable trove of indelible character studies he left us, written with care and heart and a profound sense of living. The kind that make you feel when you’re done laughing.

Zehme in Esquire: A Primer

“It’s Reege’s World. We Just Live In It” (June 1994)

“And Then There Was One” (March 1996)

“The Sidekick in Me” (June 1997)

“Daveheart” (May 2000)

“Tom Hanks Acts Like a Man” (September 2001)

“The Man Who Retired” (June 2002)

“The Confessions of Bob Greene” (April 2003)