The Canadian commandos are the first to jump. Our plane reaches an altitude of about eight thousand feet; the back door opens. Although it's a warm winter day below in rural southern California, up here, not so much. In whooshes freezing air and the cold reality that this is actually happening. Out drop the eight commandos, all in black-and-red camouflage, one after the other. For them it's a training exercise, and Jesus, these crazy bastards are stoked. The last Canuck to exit into the nothingness is a freakishly tall stud with a crew cut and a handlebar mustache; just before he leaps, he flashes a smile our way. Yeah, yeah, we get it: You're a badass.

Moments later, the plane's at ten thousand feet, and the next to go are a Middle Eastern couple in their late thirties. These two can't wait. They are ecstatic. Skydiving is clearly a thing for them. Why? I can't help thinking. Is it like foreplay? Do they rush off to the car after landing and get it on in the parking lot? They give us the thumbs-up and they're gone.

Just like that, we're at 12,500 feet and it's our turn. Me and Chris Evans, recognized throughout the universe as the star of the Marvel-comic-book-inspired Captain America and Avengers movies. The five films in the series, which began in 2011 with Captain America: The First Avenger, have grossed more than $4 billion.

The two of us, plus four crew members, are the only ones left in the back of the plane. Over the loud drone of the twin propellers, one of the crew members shouts, "Okay, who's going first?"

Evans and I are seated on benches opposite each other. Neither of us answers. I look at him; he looks at me. I feel like I've swallowed a live rat. Evans is over there, all Captain America cool, smiling away.

While we were waiting to board the plane, Evans told me that as he lay in bed the night before, "I started exploring the sensation of 'What if the chute doesn't open?'. . ."

Oh, did you now?

". . .Those last minutes where you know." As in you know you're going to fatally splat. "You're not gonna pass out; you're gonna be wide awake. So what? Do I close my eyes? Hopefully, it would be quick. Lights out. I fucking hope it would be quick. And then I was like, if you're gonna do it, let's just pretend there is no way this is going to go wrong. Just really embrace it and jump out of that plane with gusto." Evans also shared that he'd looked up the rate of skydiving fatalities. "It's, like, 0.006 fatalities per one thousand jumps. So I figure our odds are pretty good."

Again the crew member shouts, "Who's going first?"

Again I look at Evans; again he looks at me. The rat is running circles in my belly.

I look at Evans; he looks at me.

Another crew member asks, "So whose idea was this, anyway?"

That's an excellent question.

I ask Evans the same thing when we first meet, the evening before our jump, at his house. He lives atop the Hollywood Hills, in a modern-contemporary ranch in the center of a Japanese-style garden. The place has the vibe of an L.A. meditation retreat—there's even a little Buddha statue on the front step.

The dude who opens the front door is in jeans, a T-shirt, and Nikes; he has on a black ball cap with the NASA logo, and his beard is substantial enough that for a second it's hard to be sure this is the same guy who plays the baby-faced superhero. Our handshake in the doorway is interrupted when his dog rockets toward my crotch. Evans is sorry about that.

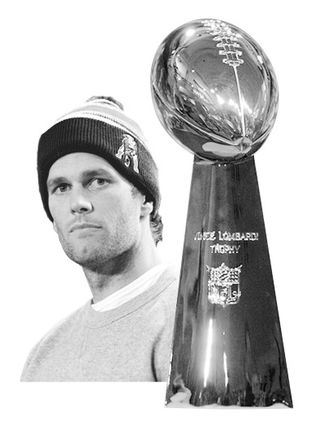

We do the small-talk thing. Evans is from a suburb of Boston, one of four kids raised by Dad, a dentist, and Mom, who ran a community theater. The point is, he's a Patriots fan, and with Super Bowl LI, between the Pats and the Falcons, just a few days away at the time, it's about the only thing on his mind. You bet your Sam Adams–guzzling ass he's going to the game in Houston. "Oh my God," he says, doing a little dance. "I can't believe it's this weekend."

Evans won't be rolling to SB LI with a posse of Beantown-to-Hollywood A-listers like Mark Wahlberg, Matt Damon, and Ben Affleck. For the record, he's never met Damon, and his only interaction with Wahlberg was a couple years ago at a Patriots event. Evans has, however, humiliated himself in front of Affleck.

Around 2006, Evans met with Affleck to talk about Gone Baby Gone, which Affleck was directing. Evans was walking down a hallway, looking for the room where they were supposed to meet. Walking by an open office, he heard Affleck, in that thick Boston accent of his, shout, "There he is!" (Evans does a perfect Affleck impersonation.)

By then, Evans had hit the big time for his turn as the Human Torch, Johnny Storm, in 2005's Fantastic Four, but he still got starstruck. As he tells it, "First thing I say to him: 'Am I going to be okay where I parked?' He was like, 'Where did you park?' I said, 'At a meter.' And he was like, 'Did you put money in the meter?' And I said, 'Yep.' And he says, 'Well, I think you'll be okay.' I was like, this is off to a great fucking start." Stating the obvious here: Evans did not get the part.

No, Evans will be heading to the Super Bowl with his brother and three of his closest buddies. Like any self-respecting Pats fan, Evans is super-wicked pissed at NFL commissioner Roger Goodell for imposing that suspension on Tom Brady for Deflategate. Grabbing two beers from a fridge that's otherwise basically empty, Evans says, "I just want to see Goodell hand the trophy to Brady. Goodell. Piece of shit."

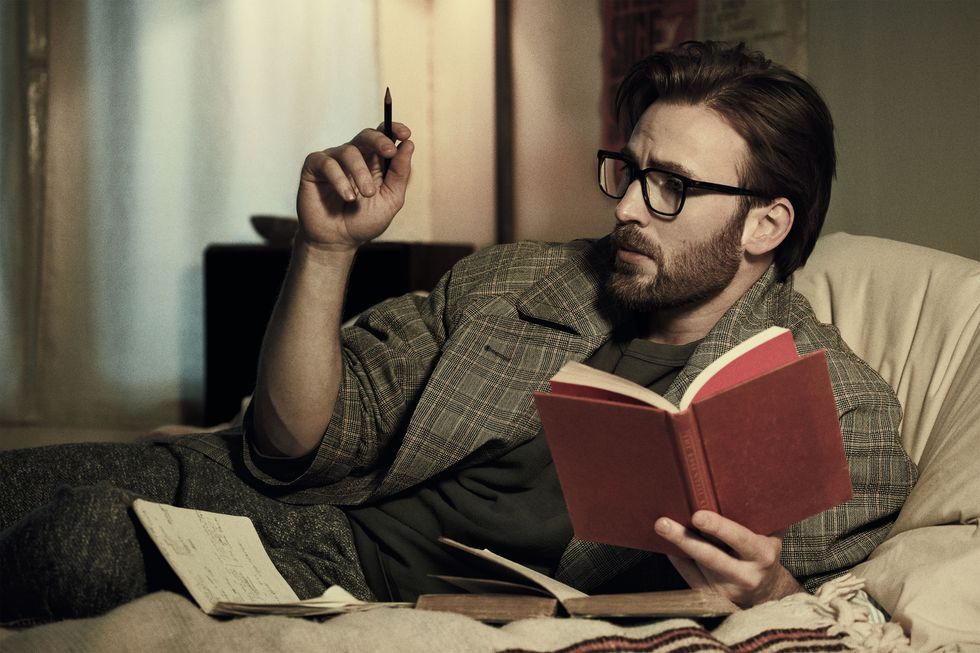

In Evans's living room, there's not a single hint of his Captain Americaness. Earth tones, tables that appear to be made of reclaimed wood. Open. Uncluttered. Glass doors open onto a backyard with a stunning view of the Hills. Evans stretches out on one of two couches. I take the other and ask, "Just whose idea was it to jump?" Since we both know whose idea it wasn't, we both know that what I'm really asking is Why? Why, dude, do you want to jump (with me) from a goddamn airplane? "Yeah," he says, popping open his beer, "I don't know what I was thinking."

Settling in on the couch, he groans. Evans explains that he's hurting all over because he just started his workout routine the day before to get in shape for the next two Captain America films. The movies will be shot back to back beginning in April. After that, no more red- white-and-blue costume for the thirty-five-year-old. He will have fulfilled his contract.

Back in 2010, Marvel presented Evans with a nine-picture deal. He insisted he'd sign on for no more than six. Some family members thought he was nuts to dial back such a secure and lucrative gig. Evans saw it differently.

It takes five months to shoot a Marvel movie, and when you tack on the promotional obligations for each one, well, shit, man. Evans knew that for as long as he was bound to Captain America, he would have little time to take on other projects. He wanted to direct, he wanted to play other characters—roles that were more human—like the lead in Gifted, which will hit theaters this month. The script had brought him to tears. Evans managed to squeeze the movie in between Captain America and Avengers films.

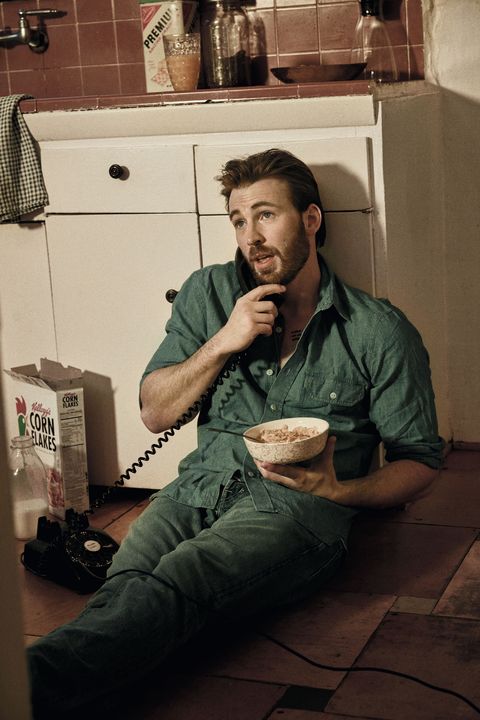

In Gifted, Evans stars as Frank Adler. You don't get much more human than Adler, a grease-under-his-nails boat-engine mechanic living the bachelor life in Florida. After a series of tragic circumstances, Adler becomes a surrogate father to his niece, Mary, a first-grader with the IQ of Einstein. He recognizes that Mary is a little genius, and he does his best to prevent anyone else from noticing. Given the aforementioned circumstances, Adler has witnessed what can happen when a kid with a brilliant mind is pushed too hard too quickly. Then along comes Mary's teacher. She discovers the child's gift, and a Kramer vs. Kramer–esque drama ensues.

During a moment in the film when things aren't going Adler's way, he sarcastically refers to himself as a "fucking hero." Evans says the line didn't lead him to make comparisons between superhero Steve Rogers (aka Captain America) and Everyman hero Frank Adler. But now that you mention it . . .

"With Steve Rogers," Evans says, "even though you're on a giant movie with a huge budget and strange costumes, you're still on a hunt for the truth of the character." That said, "with Adler, it's nice to play someone relatable. I think Julianne Moore said, 'The audience doesn't come to see you; they come to see themselves.' Adler is someone you can hold up as a mirror for someone in the audience. They'll be able to far more easily identify with Frank Adler than Steve Rogers."

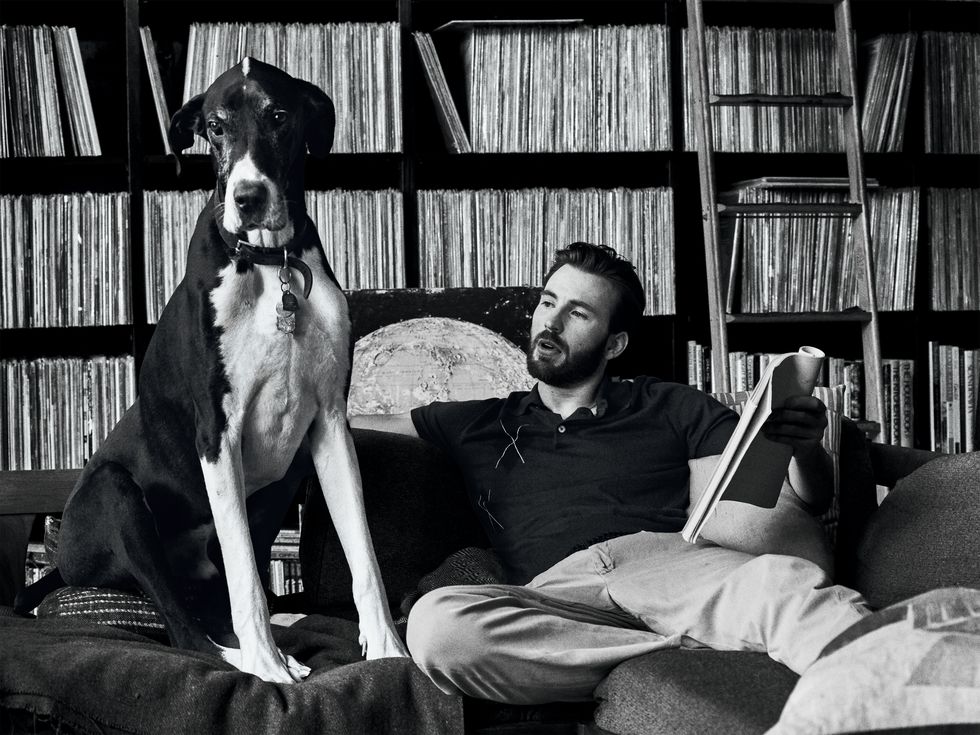

Dodger. That's the name of Evans's dog, the one who headbutted my nuts and has since done a marvelous job of making amends by nuzzling against me on the couch. Evans got him while he was filming Gifted; one of the last scenes was shot in an animal shelter in Georgia. Evans had wanted a dog ever since his last pooch died in 2012. Then he found himself walking the aisles of this pound, and there was this mixed-breed boxer, wagging his tail and looking like he belonged with Evans.

Dodger is not exactly a name you'd think a die-hard Boston sports fan would pick. His boys from back home have given him a ton of shit over it. But he has not abandoned his Red Sox for the L.A. team. As a kid, he loved the Disney animated movie Oliver & Company, and his favorite character was Dodger. Anticipating the grief he was going to get from his pals, Evans considered other names. "You could name your dog Doorknob," he says, "and in a month he's fucking Doorknob." Evans's mom convinced him to go with his gut.

Right around when Evans was wrapping Gifted and heading back to L.A. with Dodger, the 2016 presidential campaign was still in that phase when no one, including the actor—a Hillary Clinton supporter—thought Trump had a shot. He still can't believe Trump won.

"I feel rage," he says. "I feel fury. It's unbelievable. People were just so desperate to hear someone say that someone is to blame. They were just so happy to hear that someone was angry. Hear someone say that Washington sucks. They just want something new without actually understanding. I mean, guys like Steve Bannon—Steve Bannon!—this man has no place in politics."

Evans has made, and continues to make, his political views known on Twitter. He tweeted that Trump ought to "stop energizing lies," and he recently ended up in a heated Twitter debate with former KKK leader David Duke over Trump's pick of Jeff Sessions for attorney general. Duke baselessly accused Evans of being anti-Semitic; Evans encouraged Duke to try love: "It's stronger than hate. It unites us. I promise it's in you under the anger and fear." Making political statements and engaging in such public exchanges is a rather risky thing for the star of Captain America to do. Yes, advisors have said as much to him. "Look, I'm in a business where you've got to sell tickets," he says. "But, my God, I would not be able to look at myself in the mirror if I felt strongly about something and didn't speak up. I think it's about how you speak up. We're allowed to disagree. If I state my case and people don't want to go see my movies as a result, I'm okay with that."

Trump. Bannon. Politics. Now Evans is animated. He gets off the couch, walks out onto his porch, and lights a cigarette. "Some people say, 'Don't you see what's happening? It's time to yell,' " Evans says. "Yeah, I see it, and it's time for calm. Because not everyone who voted for Trump is going to be some horrible bigot. There are a lot of people in that middle; those are the people you can't lose your credibility with. If you're trying to change minds, by spewing too much rhetoric you can easily become white noise."

Evans has a pretty remarkable "How I got to Hollywood" story.

During his junior year of high school, he knew he wanted to act. He was doing it a lot. In school. At his mom's theater. He loved it. "When you're doing a play at thirteen years old and have opening night? None of my friends had opening nights. 'I can't have a sleepover, guys; I have an opening night tonight.' "

That same year, he did a two-man play. For all of the twenty-plus plays Evans had done up to that point, preparation meant going home, memorizing lines, and doing a few run-throughs with the cast. However, for this play, Fallen Star, he and his costar would rehearse by running dialogue with each other. Hour upon hour, night after night.

Fallen Star is about two friends, one of whom has just died. As the play opens, one of the characters comes home after the funeral to find his dead friend's ghost. Evans was the ghost. Waiting backstage on opening night, he knew he didn't have every line memorized, but he had the essence and emotion of the play down. Onstage, he remembers, "I was saying the lines not because they were memorized but because the play was in me. I was believing what I was saying."

He was hooked. He wanted to do more of this kind of acting—real acting. He wanted to do films, in which the camera was right on him and he could just be the character, rather than theater, in which an actor must perform to the back of the room.

A family friend who was a television actor advised Evans that if he wanted to go to Hollywood, he needed an agent. Toward the end of his junior year, he had a ballsy request for his parents: If he found an internship with a casting agent in New York City, would they allow him to live there and cover the rent? They agreed. Evans landed a gig with Bonnie Finnegan, who was then working on the television show Spin City.

Evans chose to intern with a casting agent because he figured he had more of a chance to interact with other agents trying to get auditions for their clients.

The kid was sixteen years old.

Finnegan put Evans on the phone; his responsibilities included setting up appointments for auditions. By the end of the summer, he picked the three agents he had the best rapport with and asked each of them to give him a five-minute audition. All three said yes. After seeing his audition, all three were interested.

Evans went with the one Finnegan recommended, Bret Adams, who told Evans to return to New York for auditions in January, television pilot season. Back home, Evans doubled up on a few classes the first semester of his senior year, graduated early, and went back to New York in January. He got the same shithole apartment in Brooklyn and the same internship with Finnegan. He landed a part on the pilot Opposite Sex. Even better, the show got picked up and would start shooting in L.A. that fall.

"I know I'm going to L.A. in August," Evans says, recalling that period. "So I go home and that spring I would wake up around noon, saunter into high school just to see my buddies, and we'd go get high in the parking lot. I just fucked off. I lost my virginity that year. 1999 was one of the best years of my life." Until it wasn't.

He wasn't in L.A. for even a month when he got a call from home. His parents were divorcing. Evans never saw it coming.

Family and love and the struggles therein are part of what attracted Evans to Gifted.

"In my own life, I have a deep connection with my family and the value of those bonds," he says. "I've always loved stories about people who put their families before themselves. It's such a noble endeavor. You can't choose your family, as opposed to friends. Especially in L.A. You really get to see how friendships are put to the test; it stirs everyone's egos. But if something goes south with a friend, you have the option to say we're not friends anymore. Your family—that's your family. Trying to make that system work and trying to make it not just functional but actually enjoyable is a really challenging endeavor, and that's certainly how it is with my family."

In the plane, a decision is made.

"I want to see you jump first," Evans shouts my way.

Of course he does.

Like any respectable and legal skydiving center, Skydive Perris, which is providing us with this "experience," doesn't just strap a chute on your back. First, you go to a room for a period of instruction. Then you go to another room, where you sign away your rights.

You may be wondering how the star of a billion-dollar franchise with two pictures to shoot gets clearance to jump from an airplane—never mind the low rate of fatalities, as Evans has presented it. So am I.

"Well, they give you all these crazy insurance policies, but even if I die, what are they going to do? Sue my family? They'd probably cast some new guy at a cheaper price and save some money."

Thinking the answer is almost certainly going to be no, I ask Evans if he's ever gone skydiving before. Turns out he has, with an ex-girlfriend. Turns out that ex-girlfriend is now married to Justin Timberlake. Evans and Jessica Biel dated off and on from 2001 to 2006. They took the leap together when Biel hatched the idea for one Valentine's Day. According to media accounts, Evans was recently dating his Gifted costar Jenny Slate, who plays the teacher. "Yeah," he says, "but I'm steering clear of those questions." You can almost feel his heart pinch.

We end up broadly discussing the unique challenges an international star like Evans faces when it comes to dating, specifically the trust factor. Evans supposes that's why so many actors date other actors: "There's a certain shared life experience that is tough for someone else who's not in this industry to kind of wrap their head around," he says. "Letting someone go to work with someone for three months and they won't see them. It really, it certainly puts the relationship to the test."

In Gifted, there's a moment when Slate's character asks Adler what his greatest fear is. Frank Adler's greatest fear is that he'll ruin his niece's life. Evans's greatest fear is having regrets.

"Like always kind of wanting to be there as opposed to here. I think I'm worried all of a sudden I'll get old and have regrets, realize that I've not cultivated enough of an appreciation for the now and surrendering to the present moment."

Evans's musings have something to do with the fact that he has been reading The Surrender Experiment. "It's about the basic notion that we are only in a good mood when things are going our way," he says. "The truth is, life is going to unfold as it's going to unfold regardless of your input. If you are an active participant in that awareness, life kind of washes over you, good or bad. You kind of become Teflon a little bit to the struggles that we self-inflict."

He continues: "Our conscious minds are very spread out. We worry about the past. We worry about the future. We label. And all of that stuff just makes us very separate. What I'm trying to do is just quiet it down. Put that brain down from time to time and hope those periods of quiet and stillness get longer. When you do that, what rises from the mist is a kind of surrendering. You're more connected as opposed to being separate. A lot of the questions about destiny or fate or purpose or any of that stuff—it's not like you get answers. You just realize you didn't need the questions."

This here—this stuff about surrendering, letting life unfold, taking the leap—this is why he wanted to go skydiving. It's why that sixteen-year-old took the leap and did the summer in New York; it's why he took the leap and turned down the nine-picture deal; it's why he got Dodger. Surrender. Take the leap.

And so I go first.

Oh, one important detail: Novice jumpers like Evans and me, we don't jump solo. Thank God. Each of us is doing a tandem jump. Each of us is strapped with our back to a professional jumper's front. I'm strapped to a forty-four-year-old dude named Paul. Considering what's about to happen, I figure I should know a little something about Paul. He tells me he used to own a bar in Chicago. Evans is strapped to a young woman named Sam, who looks to be twenty-something. She's got a purplish-pink streak in her black hair and says things like "badass." In fact, Sam introduced herself by saying, "I'm Sam, but you can call me Badass."

At the plane's open door, my mind goes to my wife and two teenage sons, to those I love, and to the texts I just sent in case my chute fails. Then Paul and I—well, really mostly Paul—rock gently back and forth to build momentum to push away from the plane, to push away from all that seems sane.

Three.

Two.

One.

Holy fuck.

HOLY FUCK. This is what I scream as we free-fall from 12,500 feet, at more than a hundred miles an hour, toward the earth. Which I cannot take my eyes off of. I think about nothing. Not living. Not dying. Nothing. I simply feel . . . I have let go.

Suddenly, it all stops. I'm jerked up. Paul has pulled the chute, and it does indeed open. This is fantastic, because it means we have a much better chance of not dying. But it's also kind of a bummer. I had let go. Of everything. I had chosen to play those odds Evans had talked about. I had embraced jumping and letting life unfold.

Now I had been jerked back. I would land. Back on the earth I had been so high above and from which I had been so far removed. Back in all of it.

Once I'm on the ground, safe and in one piece, a staffer runs over and asks how I feel. I say, "I feel like Captain America."

The staffer runs over and asks Evans the same question. He says he feels great. Then he's asked another question: What was your favorite part?

"Jumping out," he says. "Jumping out is always a real thrill."

This article appears in the April '17 issue of Esquire.